On June 4, 1973, President Nixon sat in the Oval Office, earphones on his head, listening to tapes, making running observations to Alexander Haig and Ron Ziegler. He listened to himself suggesting three months earlier, on March 13, to John Dean, then still his agent, that it should be maintained that he had used the FBI “only for national security purposes.”

As he listened, Mr. Nixon commented, “Yeah. The only exception, of course, was that son-of-a-bitch Schorr. But there—actually it was national security. (Laughs) We didn’t say that. Oh, we didn’t do anything. We just ran a name check on the son-of-a-bitch.”

Maybe a name check was what the former President wanted. What he got was a full field investigation, frantically aborted, then covered up with a bogus explanation. What he also got was one more item in the impeachment litany.

It was Item 65 in the Statement of Information on surveillance activities. It was Paragraph E in the Summary of Information on Illegal Intelligence Gathering. Finally, in the Judiciary Committee’s report to the House of Representatives, it was one of the instances of abuse of presidential powers listed in Article II.

I have recently been able to supplement the Judiciary Committee’s extensive research and testimony with material from the files of the FBI, and finally have been able to piece together a comprehensive account of my mini-Watergate experience as seen from within the Nixon Administration.

That account I now offer because there are lessons about government-press relations that should not be lost in the general movement toward Watergate amnesia. The “son-of-a-bitch” reflex of a president toward an offending newsman did not start, and probably will not end, with Nixon. But, for once, it is possible to document how presidential powers were abused in intended retaliation in ways that could occur again.

The Judiciary Committee’s report summed up the operation:

DANIEL SCHORR FBI INVESTIGATION

In August, 1971, Daniel Schorr, a television commentator for the Columbia Broadcasting System, was invited to the White House to meet with the President’s staff assistants to discuss an unfavorable analysis he had made of a presidential speech. Shortly thereafter, Haldeman instructed his chief aide, Higby, to obtain an FBI background report on Schorr. The FBI conducted an extensive investigation of Schorr, interviewing 25 people in seven hours, including Schorr’s friends and employers, and members of his family. When press reports revealed that the investigation had taken place, the President’s aides fabricated and released to the press the explanation that Schorr was being considered for an appointment as an assistant to the chairman of the Council on Environmental Quality. The President knew that Schorr had never been considered for any government position. The President approved the cover story. Haldeman has testified that although he could not remember why the investigation was requested, Schorr was not being considered for federal employment.

The FBI investigation—like my appearance on White House “enemy” lists—did me no ultimate harm, thanks, perhaps, to the ineptitude with which it was handled. But in the period after I became aware of it, the episode had its disconcerting if not “chilling” effects. It complicated my relations with my employer and my news sources. I had to worry about being projected into an undesired role of administration adversary.

That concern persists. For that reason, I have waived any suit on invasion-of-privacy or other grounds, uncomfortable with the idea of a docket headed, “Daniel Schorr vs. Richard M. Nixon.” But I did want information, and I concluded, in consultation with J. Roger Wollenberg of the Washington law firm of Wilmer, Cutler & Pickering, that the Freedom of Information Act provided the appropriate vehicle.

On March 19, we applied to Clarence M. Kelley, director of the FBI, for all material in the FBI’s file dealing with the investigation of me, specifically excluding interviews and summaries since I had no desire to violate the privacy of those contacted about me.

On March 27, Kelley rejected the request on the ground that “investigations concerning possible presidential appointments are considered to be investigatory material compiled for law enforcement purposes and thereby exempt from disclosure.” One could only marvel that, at this late date, Kelley could still be talking about “possible presidential appointments.”

On April 24, we appealed to Attorney General William Saxbe, pointing out that this investigation was not conducted for legitimate law enforcement purposes, and therefore could not be exempt from disclosure.

On June 6, Saxbe, overruling the FBI director, advised that the file would be released to me “as a matter of administrative discretion.” It was delivered to Wollenberg on July 2.

The FBI investigation was set in motion on August 19, 1971, two days after I had broadcast on the CBS Evening News an analysis suggesting that President Nixon’s promise to come to the rescue of the financially-beleaguered Catholic parochial schools represented political rhetoric, unsupported by any concrete program.

The House Judiciary Committee quotes Haldeman assistant Lawrence Higby as testifying that, traveling with President Nixon and H.R. Haldeman on Aug. 19 over Wyoming, on a cross-country trip to California, he called FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover, as instructed by Haldeman, to ask for “a complete background” on me, and was later surprised to learn that the FBI had launched a full-field investigation of “the poor guy.”

Higby may have been taken aback by the wide-open nature of the investigation, but could hardly have been surprised by the fact that it had taken place. For, promptly after receiving his request, Hoover wrote to him on Aug. 20, “I am enclosing a memorandum of what our files show on Daniel Louis Schorr. I have also initiated a complete investigation of Schorr and, as soon as it is completed, I will forward it to you.”

However Higby couched his request to the late director, Hoover from the outset treated it as a crash investigation preceding a presidential appointment. His first instruction, Aug. 19, headed, “Daniel Louis Schorr, Special Inquiry,” required a completed report by Aug. 23 “without fail,” and said, “The President has requested extremely expedite applicant-type investigation of Schorr, who is being considered for presidential appointment, position not stated. Do not indicate White House interest to persons contacted.”

That message went to the FBI representative in the American Embassy in Bonn. It referred to a Who’s Who biography that listed me as chief, CBS News bureau for Germany and Central Euro, which I had indeed been until 1966. I might have been more conscientious about keeping Who’s Who up to date had I dreamed that the FBI might not be aware I had been working in Washington for five years, my presence no secret to other government agencies and to TV audiences.

Next, the FBI sent telegrams to its field offices in Washington, New York, St. Louis, Baltimore and Alexandria, Va., asking for “identities and locations of all close relatives. . . . Make certain all periods of adult life are accounted for.” The telegrams included new information, “Note: Schorr is now in U.S.”

It took until the next morning before the FBI learned that I was not just visiting. An Aug. 20 memorandum said, “Investigation this morning indicates Schorr has been transferred back to the United States and is presently residing in Washington, D.C., with his family. He is apparently assigned to the CBS Washington bureau.”

The picture of the FBI, like the Keystone Cops, charging off first in the wrong direction to Germany has its humorous side. But it also suggests that the White House did not tell Hoover the real motive for the investigation.

Interviews about my background were going forward in the United States and abroad, but in Washington, where I had finally been located, the FBI ran into trouble. The Washington field office advised that William Small, then Washington bureau chief of CBS News, when contacted about the “job” investigation, stated that “he was shocked to hear this as he had no indication that Schorr was being considered for any federal position.”

Well, I might not necessarily have told CBS of my plans to join President Nixon’s team. But other FBI reports quoted me as saying I knew of no prospective position. Puzzled, the FBI got in touch with Higby, now in San Clemente with Mr. Nixon. One can picture the astonishment. An FBI memo said, “Higby . . . advised that in view of these developments, the FBI should discontinue its investigation until we hear further from Higby.”

To FBI field offices went crisp telegrams, “Discontinue investigation immediately.”

But in the seven hours that the investigation had been “active,” 25 interviews had been conducted, and the information already collected was ordered transmitted to headquarters. After a weekend of reflection, Higby called on Monday, Aug. 23, saying, according to an FBI memo, “The investigation should be cancelled; however, requested that all information developed by the bureau to date concerning Schorr be furnished his [Higby’s] office.’’

The same day Hoover wrote Higby enclosing “a summary memorandum containing the results of the investigation.” And, doggedly sticking to its bureaucratic guns, the bureau furnished for Hoover’s file “one copy of a biographical resume concerning the appointee.” (I have asked that the file be expunged. Director Kelley says that, under regulations, he can’t.)

There the matter rested, the White House and FBI presumably hoping the case was closed.

On Nov. 10, storm signals went up. Assistant Director T.E. Bishop, in charge of public relations, reported in a memorandum to his superiors that he had been called by “Ken Clawson, a reporter for the Washington Post, who is well known to the bureau,” asking about the August investigation.

“Clawson advised Bishop,” wrote Bishop, “that the FBI might not realize it, but the FBI had been ‘used’ by someone in the White House in connection with its investigation of Schorr. Clawson said that he has been informed by a source in the White House that Schorr was never being considered for appointment to a government position and that the individual who had made the request of the FBI was aware of this but had asked the FBI to conduct an investigation, allegedly in connection with possible employment, but actually for the purpose of getting background information on Schorr in an expedite manner.”

If there was concern about possible misuse of the FBI, it is nowhere evident in the FBI file. The alarm was about impending adverse publicity. The next step was to coordinate with the White House. Here is Hoover’s memorandum of a telephone conversation at 4:18 p.m. on Nov. 10:

Honorable H.R. Haldeman, Assistant to the President, called. He said that as I may know, the Washington Post is cranking up a story on an FBI investigation of CBS correspondent Daniel Schorr and apparently the bureau has confirmed to Ken Clawson, a reporter for the Washington Post, that such an investigation was ordered by the White House.

I commented I would doubt that because my orders are to not give Clawson the time of day. Mr. Haldeman said he would be surprised if we had, but Clawson claims that he does have this confirmation from the bureau and in any event he is going apparently with the story that the White House is investigating this reporter.

Mr. Haldeman said that I may recall that there was a request for a check on him back in the middle of August and obviously the White House would have no useful purpose in getting any more publicity on it than necessary so that what he wanted to do was to be sure that we did not supply Clawson or any of the rest of the press with anything.

I told Mr. Haldeman my standing orders are not to give the time of day to him and I will check on it right away. Mr. Haldeman said that Ron Ziegler, Press Secretary, is concerned that they are going to create a repression of newsmen type of thing. I said that is the usual line.

Mr. Haldeman said he thought they would slough it off over there and if they ask any question, say they would not have anything to say as obviously information is sought on individuals at various times for various reasons such as appointments, routine checks, et cetera, and not have anything more to say and he assumes that is the position the bureau would take.

I said we will not have anything to say and I would check and let him know, as it may have been confirmed by the Public Information Office of the Department of Justice.

Clawson’s story appeared on the front page of the Washington Post on Nov. 11, and was widely quoted by news agencies. The White House moved to develop its cover story. President Nixon met with his special counsel, Charles Colson.

Before the House Judiciary Committee, Colson testified that “the suggestion was made that we respond to press inquiries by stating that he [Schorr] was being considered for a position as a press or a television consultant on matters of environmental . . . environmental matters.” Committee Counsel John Doar interrogated Colson:

Doar: The fact was that Mr. Schorr was not nor hadn’t been considered for such a position?

Colson: That is right.

Doar: And the President knew this?

Colson: Yes, sir.

Doar: And you knew this?

Colson: I did.

Doar: And Mr. Haldeman knew this?

Colson: That is correct.

Doar: And that you were directed by the President to implement the instructions by putting out this information that Mr. Schorr was being considered for a job.

Colson: I don’t know that I was instructed to put out the information, but it was decided that that would be the response and I think Mr. Ziegler actually gave that response.

Doar: When you say it was decided, you are speaking, that is a colloquialism to mean that the President decided. Isn’t that fair?

Colson: Well, it is not a general colloquialism. In this case it is.

Doar: That the President decided it?

Colson: I think the President and I decided that that would be the best way that we could work ourselves out of what looked like an embarrassing situation. . . . We decided that this would be an appropriate way to dig ourselves out of a political hole. It may very well be that I said we ought to put this out, and the President said, “fine.” It may be that he said to me, why don’t you talk to Ziegler and see if we can give this as an answer.

Next day, Nov. 12, was a busy day at the FBI. Senator Sam Ervin was proposing a hearing of his Constitutional Rights Subcommittee, and Chairman Emanuel Celler of the House Judiciary Committee wrote Attorney General John Mitchell, asking for an explanation. While preparing to join the White House in the cover-up, the bureau was busy protecting its own flank.

Hoover sent a memorandum to Mitchell summarizing the situation and displaying his own clean hands. Hoover wrote, “When we were originally requested to investigate Daniel Schorr last August by Mr. Higby, an assistant to Mr. Haldeman, it was indicated to us that he was being considered for an important position. There was no mention at any time relative to the White House being curious about the background of Schorr because of some unfavorable articles which he had written about the President and members of the White House staff.”

Presidential Counsel John Dean visited the FBI with a lot of questions about investigation procedures to help prepare a plausible position. As summarized in an FBI memo, Dean wanted to know whether there were precedents for investigations initiated before jobs were offered, whether the FBI ever disclosed the White House as the instigator of an investigation, whether the FBI would respond if questioned by a congressional committee. The replies were all reassuring, and W.R. Wannall, supervising special agent in the intelligence division, wrote that Dean did not “make or imply any criticism of the bureau’s handling of this case.” Nor, apparently, did the FBI express any criticism whatever of the White House’s handling of the case, except internally.

Wrote Wannall, “It was, however, apparent from the discussion that someone at the White House got their signals mixed and requested a full field investigation when, in fact, probably all they wanted was background information on Schorr and a check of FBI files similar to that which has previously been requested by Haldeman’s office on other news personalities.” (This was the first suggestion that I was not the first newsman Haldeman had asked the FBI to look into. Interestingly, this was the only point commented on when the FBI’s legal counsel, John A. Mintz, undertook personally to deliver the FBI file to my lawyer, Roger Wollenberg. Mintz, calling attention to the reference to “other news personalities,” volunteered that this meant routine name checks of the type made for credential purposes or for screening White House visitors. But, when Wollenberg asked whether Mintz could represent officially that no other Haldeman-instigated full investigations of newsmen had been made, Mintz said, “We do not know.” Since then the FBI has stated, “We will not furnish, affirm or acknowledge the identities of individuals on whom name checks have been made.”)

With the information John Dean had brought back to the White House, the President’s position was formulated. A news conference was called for late in the afternoon, and Mr. Nixon was ready to respond to an anticipated question. Hoover got a phone call from Haldeman with advance word of what the President would say, summarized as follows in Hoover’s memo:

. . . that he [the President] understands Mr. Schorr was being considered for a public affairs position in the area of environmental matters and there was a routine FBI investigation, but there was nothing detrimental; that the position was not offered; that no one can object to the FBI check being given him the same as to anyone else, and the only objection seems to be that he was not asked beforehand if he were interested, and that objection, to the President, makes sense; and accordingly he has ordered that whenever anyone is being considered for a Government position, he be informed beforehand and if he is not interested, consideration would be dropped; that there was no intimidation nor will there be, and to make sure, he has directed this additional safeguard be instituted.

“I told Mr. Haldeman that was a good statement,” Hoover wrote. “Mr. Haldeman says it does put the burden that before any check is run on anybody, he has to be notified, but he did not think that harms them any. I agreed.”

Hoover’s memo concludes, “Mr. Haldeman thanked me.”

As luck would have it, Mr. Nixon’s Nov. 12 news conference was dominated by questions about Vietnam, and no one asked about my investigation. So, afterward, Ziegler sought out reporters and told them what the President would have said had he been asked. The wire services moved that as a story separate from the news conference.

One version caused Ziegler to make a speedy call to Hoover. Ziegler, according to Hoover’s memo, said he “understood that the UPI would carry a story to the effect that the President had said that the investigation of Daniel Schorr had been clumsily handled. Mr. Ziegler wanted to assure me that no such statement had been made by the President and the proposed story by the United Press would be inaccurate.”

Clearly, this was no time to alienate Hoover.

Peace descended on the Schorr file in the FBI for a time. Then there was a new flurry of paper at the end of 1971. The Department of the Army, which had sounded me out about speaking at the 1972 annual War College seminar, asked the FBI for one of those routine “name checks.” But nothing about me seemed routine to the FBI. It referred the Army to the White House, and on Jan. 5, 1972, Hoover advised Haldeman in a letter, “We are making no comment concerning the investigation we conducted regarding Mr. Schorr, and the Department of the Army is being referred to the White House.” What the White House told the Army, I do not know, but the invitation to the War College never came.

Activity in the FBI stirred anew at the end of January as Sen. Ervin prepared to hold a hearing on Feb. 1. Confronted with an Ervin letter asking details about my investigation, the FBI, in a Jan. 26 internal memo, recalled the promise to Dean not to cooperate with any congressional inquiry, but said that since “our relationship with the Senator has been very cordial in the past,” it might be well to be “responsive to his inquiries.” Back came John Dean to the FBI to work things out. According to Wannall’s memo, “Dean advised that Clark MacGregor, Counsel to the President for Congressional Relations, had gone to see Ervin and asked him in effect ‘what would call him off’ . . . Ervin indicated to MacGregor that in the past, situations have arisen in which the FBI has presented the facts to him which have fully satisfied his interest in a particular matter. . . . Dean feels that a letter to Ervin simply stating the facts might well close this matter as far as Ervin is concerned. Dean said that in view of the extreme sensitivity of this matter to the White House the White House would like to have the opportunity to review our letter to Ervin before it is sent.”

Dean later advised that he had discussed the draft letter with Haldeman, who suggested no changes. Hoover also sent a copy to Attorney General Mitchell, noting that it had been “cleared with Honorable H.R. Haldeman and Honorable John M. Dean III of the White House.”

So, in a Jan. 27 letter, Hoover assured Sen. Ervin that “the investigation was requested as a routine background investigation for possible federal appointment in which we make inquiries regarding a person’s character, loyalty, general standing, and ability. The incomplete investigation of Mr. Schorr was entirely favorable to him and the results were furnished to the White House.”

Hoover, of course, knew a lot more, but was not about to rock the boat. Sen. Ervin accepted his explanation at face value. The last document in the FBI file, as released to me, is a letter from Ervin to Hoover on Feb. 3, saying, “The FBI certainly did not do anything except its legal duty in initiating the investigation of Mr. Schorr at the insistence of some official in the White House.”

I had to worry about being projected into an undesired role of administration adversary.

So, my mini-Watergate conformed to the pattern of the larger Watergate conspiracy—the plot, the goof, the cover-up. The fourth element—the unraveling—was to come some 16 months later in the testimony of Dean and Haldeman before the Senate Watergate Committee.

I know now that Mr. Nixon himself wanted an FBI report on me, for reasons that can only be surmised, and that he personally approved the cover-up plan suggested by Colson. What I have not known until now is how far the FBI went in cooperating with the cover-up, and how little concern it showed about the White House abuse of its investigative powers.

There remains to be investigated, though Mr. Nixon said I was “the only exception,” what other newsmen Haldeman had the FBI investigate.

Why did the White House’s desire for a quiet, covert investigation of me become translated by Hoover into a wide-open full-field job investigation that brought embarrassment to the White House? I still do not have the answer, and perhaps, with Hoover dead, I never shall.

My mini-Watergate was only one facet in a much larger picture. But I recall the remark of Max Frankel, then Washington bureau chief of the New York Times, who knew about the FBI investigation of me from the outset.

“I’ll never forgive myself,” he said, “for not sensing that such an investigation could not be an isolated event but had to be part of something much bigger.”

But, if Mr. Nixon did not succeed in what he originally had in mind, he did accomplish one thing. He made me part of the story instead of simply the observer. He forced me to submit to a thousand jokes about whether my FBI “shadow” was still with me, and whether it was safe to talk to me on the telephone. He made me worry about whether I was still perceived by the public as an objective reporter, and whether I might be a source of embarrassment to my own news organization in its conflicts with the government.

There are many kinds of “chilling effects” on the exercise of press freedom. Whenever a president uses the powers entrusted to him to go after a reporter, there are bound to be some.

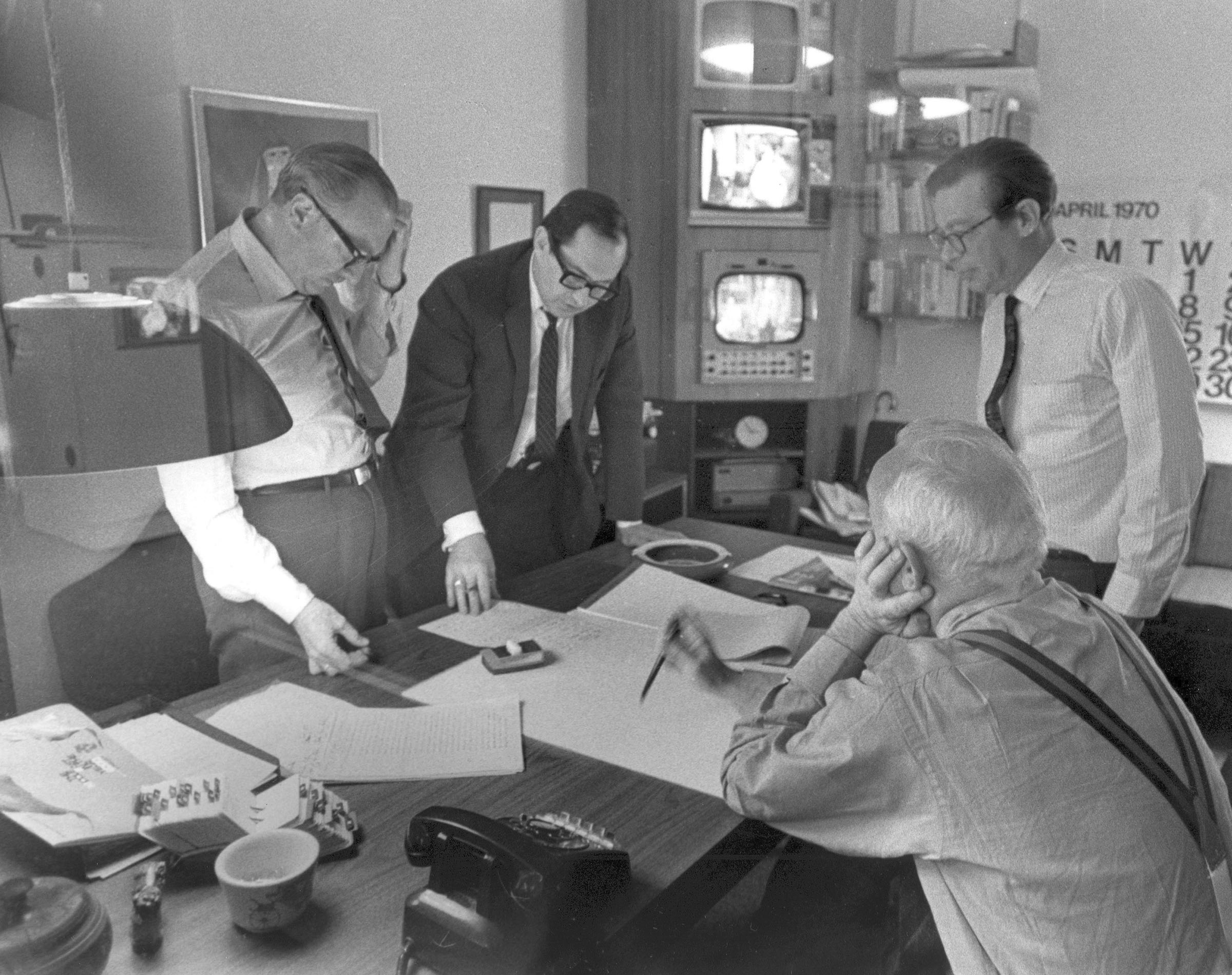

TOP IMAGE: Daniel Schorr, Walter Cronkite, and two producers in New York, April 1970; Photo by CBS Photo Archive/Getty Images