A couple of weeks after I had my first baby a friend called to see how I was doing. My husband chatted with her on the phone in the dining room—“Oh, she’s feeling great”—while I sobbed hysterically in the living room. He wasn’t lying: physically, I was okay. I was just on the verge of sinking into journalistic oblivion.

My husband, who is also a writer, had another reason to celebrate besides our daughter’s arrival—his first assignment from The Village Voice. It was five years ago, unemployment was soaring, and he was about to start what turned out to be a front-page Labor Day piece on the sad odyssey of job hunting in New York with no skills. (One vague want ad called for “men (small).” He applied, only to be rejected because he was too big to clean the grease out of air-conditioning ducts.)

It was a dream assignment, but while he was going to be out reporting, I was going to be at home, alone for the first time in my life with a tiny baby, in this case one that cried until she turned purple. I was convinced that my career was over. My worst-case scenario was coming true: my husband would become a star, and I would spend the rest of my life trying to catch up.

It’s easy to see now how ridiculous I was being, but at the time those feelings were real. I was overreacting, of course. But maybe my fears also had something to do with the nature of the news business. A woman has to prove herself from day one—that she’s tough enough, competitive enough, aggressive enough. She works those long, hard hours all those years, and then all of a sudden she decides to have a baby and it’s like slamming on the brakes.

Jane Eisner, now associate editor of The Philadelphia Inquirer’s editorial page, was a city hall reporter when she became pregnant with her first child. She still hadn’t told anyone about her condition when she was asked to take on a special assignment that would have required a lot of work several months down the road. “I really would have loved to do it,” she says. “Instead, I blurted out, ‘But I’m going to have a baby.’ The editors said, ‘Oh.’ I went home and just cried.” She was so anxious to keep her hand in things that, during her first maternity leave, she did some stringing for Time.

That sense of missing out, and of needing to prove they can still go the distance, drives some women to return to work very quickly after they’ve had their babies. Judi Hasson was a congressional reporter for United Press International when she had her son. She could have taken up to two years’ leave without pay but she chose not to. “I worked till the day I gave birth and came back nine weeks later,” says Hasson, who is now with the Gannett News Service in Washington. “It was my own need to feel I was still a journalist. Some of my male colleagues said, ‘How can you be a mother and come back?’ I wanted to show the world this wouldn’t interfere with my job as a professional. In retrospect, I could have done that four months later, too.”

Sometimes the feeling of being out of it, of being sidelined, can linger for years. “I’m not in retirement,” says Laura Kiernan, who was a reporter for The Washington Post before moving to New Hampshire to raise her family. She taught and freelanced and then worked part time for the Post’s national desk before being hired last year as a reporter for The Boston Globe’s weekly New Hampshire section, a job she loves. But she says the demands of her two small children have slowed her pace considerably. She’s just trying to keep her head above water until they are in school and she can go at it full-tilt again. “I worry a lot about whether people will feel I’ve disappeared,” she says. “You have to maintain some degree of visibility. If you start to fade, you’re done for.”

Almost every woman I interviewed for this story said she had experienced some sort of career-related stress in becoming a parent. These women talked about all kinds of tensions and pressures, including the personal anxiety I experienced, the wrestling with ambition that can take a long time to resolve. Sometimes the worrying eventually proves unnecessary. Jane Eisner at the Inquirer returned from her first maternity leave to be named city hall bureau chief. Soon after, she was sent to London, the paper’s first mother to be named a foreign correspondent. After her second maternity leave, she was given charge of the op-ed page. “Having children hasn’t hurt my career,” she says, although she adds that there have been times when her career has taken a toll on her family life.

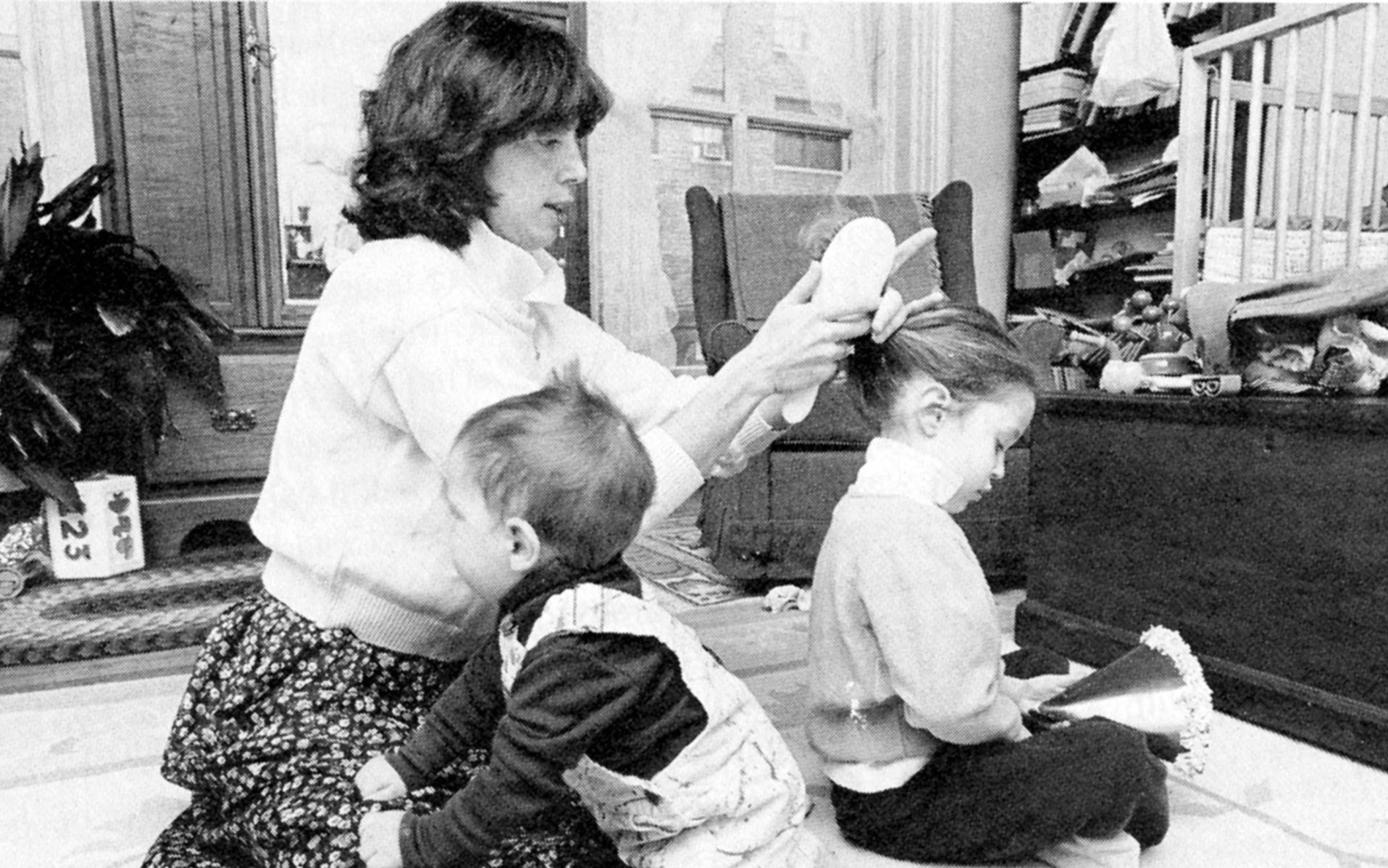

But other women are not sure they will ever get back on the fast track. Melissa Dribben was hired by The Record in Hackensack, New Jersey, when she was pregnant with her first child. She started work when the baby was five months old. “It was the most stressful period in my life,” she says. “I was starting a new job, covering meetings at night, getting home at two or three in the morning. I remember leaving for work, walking down the stairs, saying good-bye, and crying. But I was really ambitious. I wanted to get ahead, and it paid off. I got promoted quickly.” Now she has another child and the pull of her family is even greater. She works three days a week, sharing a full-time job with another reporter. “This is the biggest source of conflict in my life,” she says, “all those years of wanting a career, and now I want two things just as much. How little you can let your family compromise your ambition is the name of the game. I’m afraid I won’t get to where I want to get to, but I’m not willing to compromise my kids.”

Some of this stress, the “I’ll never win a Pulitzer” kind, is probably unavoidable. A lot of hardworking professional women in all kinds of fields have a hard time adjusting to the limits imposed by having children. At some point they come to terms with their priorities and their family needs and then get their working lives in order. But many of the stresses that were described to me—the kind that relate directly to what goes on in the office and go far beyond any individual worries about ambition—could be prevented.

Some of these stresses are caused by what workplace experts call “the culture of the industry,” both the myths and the realities of how the journalism business is run in this country. And some of them are caused by newsroom policies, both official and unofficial, including those that are ostensibly made for the benefit of women but may actually do them more harm than good.

This is new territory for many newspapers. Some of the women I talked to said they are the first women to have children at their papers, and it is their experiences, for better or worse, that are setting the precedents for the women who come after them. Other papers are literally booming with babies: half a dozen or more women may be pregnant in the newsroom at one time, as the women who entered the profession ten to fifteen years ago reach their middle to late thirties and decide to start families. But there isn’t always strength in those numbers. Editors may promote one reporter who comes back from maternity leave and demote another. They may allow one reporter to share a job and work part-time while forcing another to work nights. The issues of maternity leave and job status are a whole new battleground for women who thought their biggest fights—breaking into the profession and proving their skills—were behind them.

How accommodating is the American newsroom to new mothers? The three most important factors in keeping stress to a minimum seem to be an adequate leave, satisfactory child care, and being able to return to the same job or a comparable one that fits both the paper’s and the employee’s needs. From my small random sampling, I’ve come to the conclusion that a newspaper can be one of the best places for a new parent to work. It can also be one of the worst. There are papers that bend over backwards to help new parents feel happy and productive, and there are papers that are run like sweatshops. In between are the majority, places where the editors may not be slave drivers, but aren’t all that understanding either.

Given the fact that papers are hiring women in greater numbers than ever before, women who are talented and ambitious and don’t plan to stop working if they have children, isn’t it in the papers’ best interest to take some steps, having invested in these women in the first place, to keep them? “Forty percent of our hires over the past couple of years have been women,” says Arlene Morgan, deputy metro editor at The Philadelphia Inquirer. “Most of them are married. They are valuable and talented. You want to have them come back.”

It’s important to note first that maternity leave policies in general in this country are dismal. The United States is the only major industrialized nation that does not have some form of national, partially paid maternity-related benefits. Over 100 countries do, and nine European Community countries provide paid parental leave to both men and women. At home, almost all of the top American companies responding to a 1986 survey said they offered short-term paid disability benefits, usually six to eight weeks following a normal birth. But only 52 percent said they offered any additional unpaid maternity leave. In fact, more may offer it, says Margaret Meiers, a senior associate at Catalyst, the research group that conducted the survey, but they may do so selectively. “If they like a woman and think she’s a good employee, they’ll give her a longer leave,” says Meiers. “If they don’t like her, they won’t.”

I found that little solid research has been done on maternity benefits at newspapers—and there is an urgent need for reliable studies—but it’s safe to say that there is a wide range of paid and unpaid leaves. The New York Times, for example, offers a leave of up to six months, partially paid. So does The Sacramento Bee. The Austin, Texas, American-Statesman allows its employees to use whatever vacation and sick leave they have, but they are allowed to take only as much time as the doctor says they need.

In general, it seems that a few lucky reporters and editors may be able to take up to a year or more off, with some of that time paid, depending on seniority and how much vacation and sick leave they use, while others are expected to be back at their desks as soon as six weeks after they deliver. A pregnant reporter at one small daily who told her editors she would be taking her full six weeks says they acted surprised. “They said, ‘You’re not going to take all that, are you? We’re pretty shorthanded.’ ”

At another small paper, this one in California, the publisher told me proudly that her city editor had just come back from having a baby and was actually breast-feeding it on what she described as an “incredibly stressful” job. The editor was working nights and her husband was bringing the baby in to be nursed. This woman had been home for six weeks after the baby was born, the length of time she was allowed following delivery under the paper’s official maternity leave policy, the publisher said. However, she added that employees could take a leave of absence beyond that of up to six months, depending on how long they felt they needed to be at home, their particular job, and the length of their service. In this way, she said, the leave could be tailored to both the new mother’s and the paper’s needs. (That sounds fine, but I wonder whether a less enlightened management might be tempted to use such discretionary leave to play favorites.)

How long is the ideal maternity leave? Six weeks may be time enough for a physical recovery, but there are other considerations. What about the emotional needs of the mother and the child? And how many babies are sleeping through the night at six weeks? The Sun Herald, a daily in Biloxi, Mississippi, with a weekday circulation of 49,000 and a newsroom staff of twenty-four reporters, offers its pregnant employees up to four months’ leave, with at least part of that period paid. “We feel that’s enough time to recuperate and be with the newborn,” says personnel director Toni Dutruch. “By then, you’re adjusted and you’re getting more sleep. Six weeks is not enough time to come back. You won’t be happy or productive.”

But six weeks is all that many journalists get. The woman who told me the following story was not complaining, although she had every reason to. She was doing her job the best she could, but I found the conditions she was working under this past winter shocking. She asked that her name not be used because she was afraid of losing her job, which is a combination of editing and reporting at a paper with a circulation of under 15,000.

I spoke to her when her baby was seven weeks old and she had been back to work one week. The first day back she worked ten hours; the second day, twelve hours. That week she worked six days. She said she was averaging three to five hours of sleep a night. And with such long hours and such a small baby, she was having trouble finding child care. “The baby’s only seven weeks old and I’m on the third babysitter,” she said. In fact, the baby was sick the day I talked to her, and the child’s grandmother, who lived nearby, had taken a day off from her job to take care of it.

This woman is divorced, has two children, and needs to work, and she certainly hasn’t taken advantage of her situation. She has been at her present job seven years. “With my first baby, I worked till Friday and had her on Saturday,” she said. “The next time I worked till Friday and had the baby on Sunday.” She said she felt under a lot of pressure. “You have to be here. I think I’m overcompensating. But I feel they’re keeping watch. You have to show you can do it all.”

“You have to maintain some degree of visibility. If you start to fade, you’re done for.”

When I started researching this story I had no particular leads on women in stressful situations. I just started calling papers at random, asking for anyone with a new baby or small children. Especially at small papers, it was as though I had tapped a vein, and the stories just poured out. That may be some indication of how widespread these situations are. A reporter I spoke to at a small southern daily resumed her job full-time only five weeks after her baby was born, covering a beat that takes in three rural counties and requires her to be on the road at least two days a week, six to eight hours at a time. She works at home with a computer and says she’s been able to arrange her schedule so that she is not exhausted and can spend time with her baby.

As the first woman in her newsroom to become pregnant, this reporter says she felt under great pressure to set a precedent that showed she could handle it. She fought while she was still pregnant to keep her beat instead of being reassigned to a desk job, not only because she liked it but also because it gave her some degree of autonomy and a sense of control in her personal and professional life. “I was showing that my mind didn’t go dead, that I wasn’t putting up wallpaper instead of working, that I was responsible.”

She says the biggest obstacle she was up against was “this macho attitude, that to be a good reporter everything must be second; husband and family are negligible. When you bring a child into that atmosphere you feel like a real freak. I tried so hard to make arrangements so that I would not be seen as performing poorly, so they couldn’t say, ‘See, if you get pregnant, you can’t perform.’ ”

However, when the next reporter became pregnant last year the editor instituted a new policy that all pregnant women would be brought into in-city assignments, to minimize the paper’s liability. That second reporter was given a life-style assignment. “She had been covering government, politics, and crime,” says her co-worker. “Now, one of her jobs is working on wedding stories.”

What about that macho attitude, that hardbitten Hello-sweetheart-get-me-rewrite image, the notion that the news waits for no one and a reporter must be ready to go anywhere anytime in search of a story? “In that case,” says Anna Padia, human rights coordinator for The Newspaper Guild, “don’t take a vacation or get sick. In fact, why not move into the damned plant? Just give up your whole life and live for the profession twenty-four hours a day. There’s a mythology that’s been inculcated over the years into our minds and bloodstreams that we’re different. But journalists are human beings: fathers and mothers, churchgoers and PTA members. Firefighters, engineers, teachers, and doctors don’t give up those rights. We don’t owe our souls to the company store.”

However, that line of thinking still prevails, Padia adds, and therefore the interruptions of pregnancy penalize women just for being female. “It’s a terrible conflict,” she says.

Just how terrible a conflict is illustrated by the story of another woman who asked that I not use her name, even though she no longer works in journalism. She left her paper two years ago, but she still can’t talk about her experience without crying. She was city editor when she took her first three-month maternity leave, “some vacation and the rest unpaid,” in 1981. She was living-section editor when she became pregnant again, and it was then she learned that a 1978 federal law entitled her to include her accumulated sick leave, which amounted to several weeks, in her maternity leave. But she says when she asked management about it and then her union representative, she was told she couldn’t. She says the union steward told her, “That’s not what sick leaves are for.” She called a lawyer, and the paper then agreed to let her take it. But she believes she paid a price for asserting herself.

When she was about to come back from the second leave, she says she was told her day editing job was no longer open and she would have to work nights. She was surprised, she says, because “there had been no criticism of my work performance before that.” Relying on a state law that guarantees women returning from maternity leave the same or a similar job, she again sought outside legal help and was given her old job, with a written agreement guaranteeing her daytime employment for one year. When the year was up, she was again offered nights and weekends, hours she says management knew she couldn’t work because her husband is out of town a lot. She chose to quit.

“I had to choose between my family and work, and that’s when my career ended after six years,” she says. “I’m really bitter and hurt by it. Despite the attitude there, I loved the work.” Because there is no other newspaper in her city, she feels shut out of her profession, and she misses it. “I’ve allowed myself to dream that, if the management at the paper changed, I’d approach them again.”

Child care is another area where new parents do not get much help from their papers, although a small but growing number of businesses of all kinds are realizing that such help can pay off in lower absenteeism and better morale. While finding good, reliable child care is always a problem, it can be particularly hard for reporters and editors who work unpredictable hours. Janet Davey is one of only two reporters at The Daily Herald in Columbia, Tennessee (circulation 13,000), and she covers a lot of meetings in the afternoons and sometimes at night. One of her two young children goes to a day-care center, which closes at 5:30 p.m. “Most of the time, two hours before a night meeting I’m having a heart attack,” she says, “scrambling at the last minute to find a sitter. My husband is unreliable; he doesn’t like to do it.” If she is out sick, she gets paid, but if her children are sick and she misses work, she doesn’t. “Sometimes, if they’re sick, I’ll get someone to watch them in the morning until eight. Then I’ll try to get in the office at six-thirty or seven a.m. to work for an hour or so. I can get a lot done then.”

The biggest obstacle she was up against: “This macho attitude, that to be a good reporter everything must be second; family is negligible.”

In 1979, 34 percent of women with children under the age of one were in the workforce. By 1986, that figure had jumped to 52 percent. There are some signs that both society and the workplace are coming to terms with those numbers, although at a pace that makes a snail look like a jogger. A bill now before Congress would create a national family-leave policy, giving new parents up to ten weeks of unpaid leave in all companies with fifty or more employees. That’s not much help to people who can’t afford to go without a paycheck for that long, but at least it’s a beginning. There is also comprehensive child-care legislation under consideration on the Hill, including a bill introduced by none other than arch-conservative Senator Orrin Hatch.

In the workplace women and a handful of men have begun to push in the last few years for arrangements that give them more time with their families—job-sharing, flexible hours, four-day work weeks, working from home—and some of this is beginning to be done at newspapers. At The Record in Hackensack, New Jersey, four reporters, all women, share two full-time jobs, one in the business department and one in general news. The Daily Inter Lake, a small paper in Kalispell, Montana, has a husband-and-wife team sharing a reporting job. And the Post-Dispatch in St. Louis has William and Margaret Freivogel, who jointly share the title of assistant Washington bureau chief. Whoever is not working at the office is at home with the couple’s four children. They have been sharing a job since 1980, when they approached the paper with the idea, thinking it wouldn’t go anywhere. But management, says Bill Freivogel, “immediately saw the potential of a good deal for the company.” In essence, the Post-Dispatch got two good reporters for the price of one.

There are all kinds of good deals waiting to be worked out. Newspapers have more flexible hours than nine-to-five companies and the computer technology to allow some reporters to work from home. Given the range of jobs in the newsroom, there’s also plenty of opportunity for new parents and their editors to sit down and work out a schedule or a job definition that fits the needs of both. Judith Havemann was deputy national editor at The Washington Post when she left to have twins. When she came back, the paper created a new reporting beat for her, covering the Office of Management and Budget and another federal agency, which suited her time needs better. At the Detroit Free Press, Karen Schneider, a political reporter and editor returning from a leave, asked to work one weekend day as part of her five-day week, so she would only have to have a sitter four days. The paper obliged. “Newspapers have a golden opportunity to be leaders in policies for parents,” she says. “And that kind of consideration will pay off in terms of loyalty and dedication.”

Some people believe the next few years will see big changes in newsrooms as the next generation of managers takes over, men and especially women who are more attuned to the needs of working parents.

But Jean Gaddy Wilson, a journalism professor at the University of Missouri who has done extensive research on women in media, is not so sure things will change soon. “Only thirteen percent of the directing editors in the country”—those who make news decisions—“are women,” she says. “And that is changing at the rate of less than one percent a year. At that rate, when women achieve parity in editorships with their membership in the population, it will be the year 2055.”

The top women at many newspapers today are single or childless. Can the same be said of the top men?

Just having women in top management is no guarantee that newsroom policies will change, Wilson says. “I’ve sat in on

seminars with a lot of top women who have gotten there without having children. When the conversation turns to day care or maternity leave, they don’t want to hear about it. They want to change the subject, to talk about something ‘that really matters.’ The news business is predominantly a male structure, and those who have made it within a male structure have those values. The feminist writer Shulamith Firestone said we will only have equal access [to power] when we stop bearing children.”

But women are not going to stop having children, even though some, perhaps many, women in the news business up to now have sacrificed their personal lives for successful careers. The top women at many newspapers today are single or childless; can the same be said of the top men? The women I spoke to who are having children and returning to work see no reason why they can’t have what men have had all along—both a family and a fulfilling job. The women, however, are still the ones bearing the brunt of making that radical change. In an ideal world, it seems to me, fathers would assume an equal risk to their careers.

A handful of male journalists have taken time off from their papers to be with their babies, and a few, like Bill Freivogel at the Post-Dispatch, have actually slowed down their careers to play a bigger part in family life. “Most men I talk to will say, ‘That’s terrific, but are you getting as much as you want to out of work?’ ” Freivogel says. “The women will say, ‘Gee, I’d like to do something like that.’ ”

But few men in any field take more than a few days off when they become fathers, even when their companies offer official paternity leaves. In fact, the leave policy may be only window-dressing, not meant for those on their way up. “If you think there’s resistance to women taking time off,” says a lawyer who works on parental-leave issues, “the resistance to men who take time off is extra-ordinary. Men have been told, ‘If you do that, you’ll never get promoted.’ Some are belittled and humiliated.”

I worked with a reporter once who sat at his desk and pined for his newborn son, who came in late and often slipped out early to be with him. But it seems that most new fathers, for one reason or another, bypass the job stresses and career conflicts that new mothers face. “I think it’s just easier for men,” says Karen Schneider at the Detroit Free Press. Her husband is the paper’s television critic. He travels a lot and misses the children, she says, but he seems to take this in stride. “Men just plow ahead. They have no experience of radically modifying their lives for children.” I spoke to a woman at another newspaper who had been a reporter before her baby was born, but was now on the copy desk so she could work part-time. Her husband, meanwhile, had been promoted to assistant managing editor at the same paper. She didn’t sound upset. In fact, she said she was having too much fun with her child to worry about her career.

But I wonder if, in darker moments, she doesn’t resent it. Maybe a little? Maybe a lot.

TOP IMAGE: Melissa Dribben in 1988; Photo by Bud Glick, courtesy of photographer