One year on the Web is like seven years in any other medium,” a newsroom leader named Kevin P. McKenna told Laura Italiano in “Gimme That On-Line Religion,” her 1996 piece for the Columbia Journalism Review about the pope’s journey into cyberspace. It’s a marvelous quote for many reasons, one of which is that McKenna’s job title at the time was “editorial director for the New York Times Electronic Media Company.” It wouldn’t take long for those last three words to become superfluous.

More important, the quote conveys a key reality for the media business: Change never stops or slows down. One year is always seven years; time speeds on without a moment when transformation ends, the work is complete, and you can put your feet up. Consider how quaint McKenna’s comment feels now. Back then there was “the Web”; now we have Twitter, Facebook, Clubhouse, NFTs, and whatever form of information-sharing pops up next. And note that, when Italiano wrote her article, it was astonishing, as she reported, that 343 emails had been sent to a generic address connected to the pope. Now we’re five years past the time a fake story about the pope endorsing Donald Trump registered nearly a million engagements on Facebook.

Time speeds on without a moment when transformation ends, the work is complete, and you can put your feet up.

As shown in this collection of pieces from the CJR archives, digital technology continuously shakes up media in at least three ways. First, there is the business of journalism. It’s hard not to feel a little wistful reading Edward R. Murrow’s entreaty from the 1950s: TV news, he argued, had become an “endless outpouring of tranquilizers” aimed at pleasing advertisers. He didn’t hope to “turn television into a 27-inch wailing wall where longhairs constantly moan about the state of our culture and our defense,” he continued. “But I would just like to see it reflect, occasionally, the hard, unyielding realities of the world.”

Now the problem is the opposite. The vagaries of algorithms push the news business to become an infinite wailing wall, crowding out in a different way the reflection and sincerity that Murrow sought. Emily Bell, in 2016, described media companies as ships sailing along with, or against, the pernicious winds cast down by the gods of social networks. More recently, prestige journalism outlets have shifted toward subscription models—which seemed, at first, to take us in the direction of quality and originality. (Why else would someone give you their money?) But as it’s turned out, there are still reasons to worry. Good information is becoming more expensive, while bad information will always be free.

The second profound force is the mode of distribution. In 1958, Murrow had vastly greater influence than any journalist today; the media industry has since splintered. First came the rise of cable news. Then came the Web, which dramatically reduced startup costs for publishing. Social media followed, shifting power from newsrooms to individuals who could use Facebook and Twitter to build their own brands. And now we have newsletters, where people can turn those brands they built one tweet at a time into profitable fiefdoms.

Alissa Quart’s essay is a keen look at that phenomenon. An expert used to be someone with a credential, she observed; now an expert is anyone who’s claimed the crown. The same could be said about journalists. You used to need a credential to call yourself a journalist, and you certainly needed one to make it your life’s work. Now you can just put the title in your Twitter bio. Which model is better? Quart was wise not to tip the scales. Things were a lot simpler and smoother when Murrow called his correspondents and colleagues to set the agenda of the CBS Evening News. They are a lot more complicated and interesting now that Norah O’Donnell, his distant successor, has to pore through hundreds of Substacks—any one of which might get more attention than she does on a given day.

And third, there is the work itself. Every year, the skills required to be a successful journalist change. You have to competently report and write a draft, as has always been the case, but now you must also understand how to present your story on social media, optimize it for search, and perhaps transform it into a newsletter. Moreover, the act of reporting has evolved; journalists must navigate the vast, choppy ocean of information (and rumors and lies) that is the internet. Journalists have learned to sleuth the dark Web and find secrets buried in online data. They reverse-image-search to fact-check the origin of a photograph. They meet sources not on park benches, but on Signal. When Margaret Sullivan interviewed Philip Meyer, the father of “precision journalism,” for CJR, in 2001, he argued that all journalists needed to get over their phobias of math and machines and learn how to use a computer. We’ve finally done that, at least. But if you want a journalism job in five years, it’ll sure help to understand artificial intelligence, too.

It’s easy to read these pieces, particularly Murrow’s, and feel a certain defeatism. But that’s the wrong emotion for the moment. Better to feel excitement and curiosity about what’s to come for the media industry, and what has yet to be built. That journalism is a profession in constant reinvention is intimidating; it’s also what makes what we do beautiful. Bell wrote energetically about three new media entrants: BuzzFeed, Vox, and Fusion. At the time, they all seemed similar, and similarly promising. Two are now worth about a billion dollars, and one is totally gone. Media is a roller coaster: the downs make you queasy; the ups are thrilling; the ride is never boring. “I’m not doubled over by ‘this computer stuff’ just yet,” Italiano concluded. But, she added, “I am smiling.”

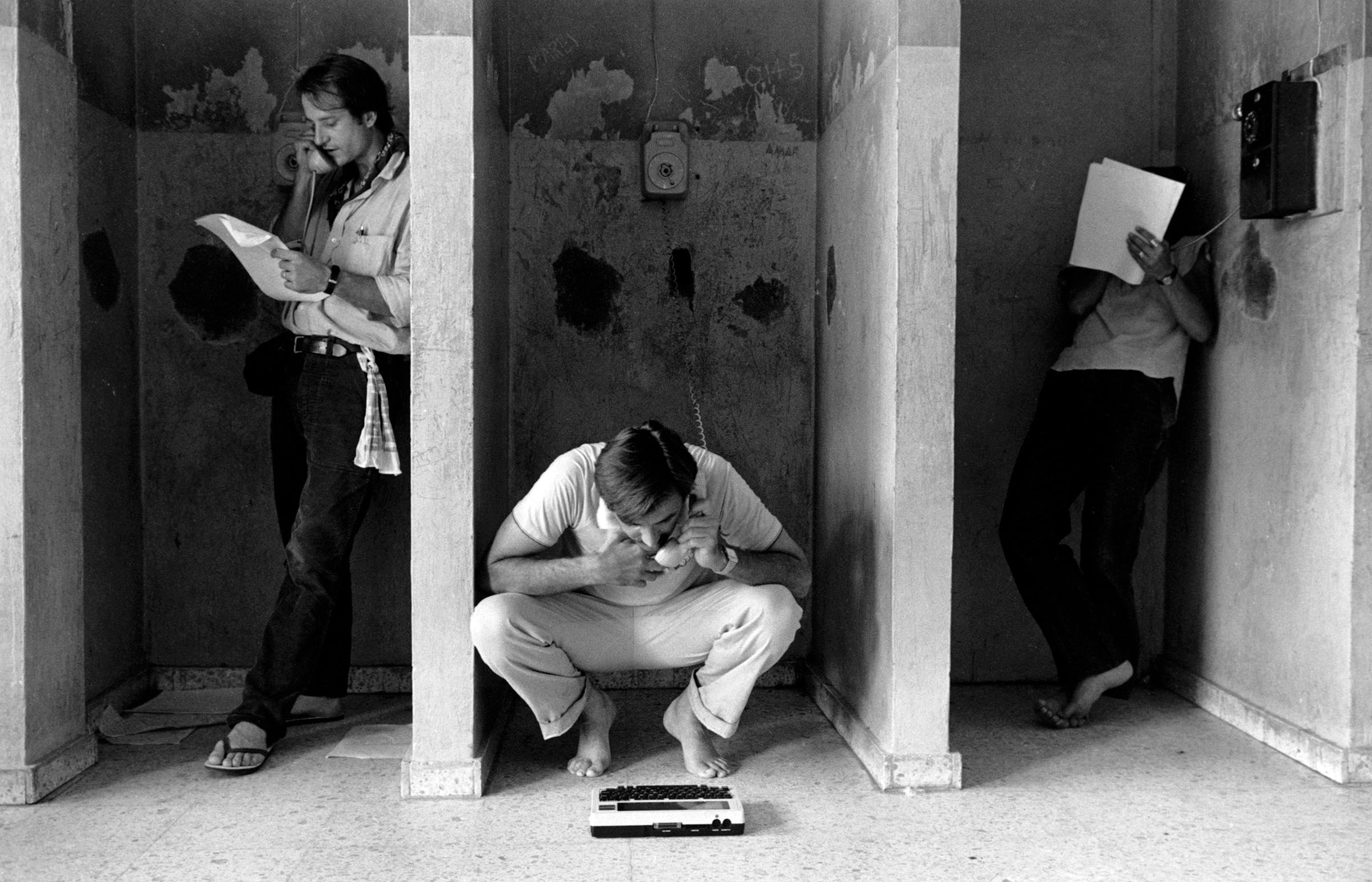

TOP IMAGE: Journalists in El Salvador, November 1964; Susan Meiselas/Magnum