“Ike, how do you know?” Bob Johnson, the AP’s Dallas bureau chief, asked James “Ike” Altgens, one of his photographers, on November 22, 1963. There were scattered reports that President John F. Kennedy, who was visiting the city, had been shot, but they hadn’t been confirmed. Johnson had begun typing a bulletin but got only as far as the dateline. His fingers were poised, waiting for information. Altgens had an answer: “I saw it. There was blood on his face. Mrs. Kennedy jumped up and cried, ‘Oh, no!’ ”

The exchange between Altgens and Johnson appears in “The Reporters’ Story,” which ran in the Columbia Journalism Review in the winter of 1964, a collection of firsthand accounts from journalists who covered the assassination as it was happening—before anyone was sure it was an assassination. It is in many ways a period piece, beginning with a description of reporters “clawing and pummeling” one another for access to a radiophone and a reference to those journalists as “men who were in the Presidential party in Dallas.” There were, in fact, women there, including Marianne Means, of Hearst Headline Service, who delivered her colleagues the information that Kennedy had been shot and was at Parkland Hospital. “When Miss Means said those eight words—I never learned who told her—I knew absolutely they were true,” Tom Kirkland, the managing editor of the Denton Record-Chronicle, said. “Everyone did. We ran for the press buses.” The riposte to “How do you know?” is another question: Whom do you trust?

To look back at the coverage of crises in the pages of this magazine is to be reminded that trust is the product of a never-ending negotiation between the press, the public, and those in power. In November 1963, White House aides pulled reporters onto Air Force One as it was about to depart from Dallas, to witness Lyndon Johnson being sworn in as president—a recognition that legitimacy could not be separated from transparency. In the winter 1968/69 issue, Thomas Whiteside looked at protests and police violence surrounding the Democratic National Convention in Chicago; a piece of evidence that the mayor, Richard Daley, had engaged in “a deliberate policy” of suppressing coverage was how hard it was for journalists to book spots in private parking lots (“usually the owners are delighted to cooperate with television networks”). It wasn’t natural; the fix must be in. Still, cameras were rolling when police started beating up demonstrators—and journalists—in Chicago’s Lincoln Park. When James Strickland, a Black cameraman, tells police he is with NBC, the reply, as rendered by CJR, is “You black mother——, we’ll kill you before the night is over.” (He lived, after being hit in the face.) And yet, a producer tells Whiteside, “whenever we put our lights on, we reduced the amount of violence in front of us.”

Many events of the past few years—notably the response to George Floyd’s murder—have supported the belief that documenting makes a difference, even if the larger ecosystem of public trust is in a precarious state. Protesters now have their own cameras; there’s hardly agreement about what journalism is. Questions of identity and purpose are not new, however; when Walter Lippmann was asked, at a seminar at the Columbia Journalism School in 1969, how the “mass media” should lay out complex issues to the public, he said, “First of all, I don’t know enough about the mass media. I know something about journalism, but I know very little about broadcasting.” What he did see left him “utterly dissatisfied almost always”; everything seemed too “dramatic.”

Trust is the product of a never-ending negotiation between the press, the public, and those in power.

Journalists haven’t sobered up; maybe they never should. When the government and press face off, each makes a bet on what the public will think. In 1961, after the Bay of Pigs debacle, Kennedy lashed out at the press for not keeping quiet in the name of national security. That tension—over not just what reporters know but what they should reveal—is a constant, as is the government’s confusion of security with its own embarrassment. In 1971, the Nixon administration got a restraining order to stop the New York Times from printing excerpts of the Pentagon Papers, whose crucial revelation was the extent to which successive administrations had lied about what was happening in Vietnam. While the Times was still fighting the order, which the Supreme Court would overturn, the Washington Post began printing excerpts. As Gloria Cooper notes, reviewing the memoir of Katharine Graham, the Post’s publisher, in 1997, that decision—with its mixture of collegiality, defiance, and sound news instinct—elevated the Post to the national stage, even before Watergate did. Cooper argues that what differentiated Katharine Graham from her husband, Philip, who had been publisher until his suicide, in 1963, was not that she had less experience but that Philip was too close to JFK. Access had distorted his understanding of his job. His wife was not, as he was, strategizing with Kennedy at the 1960 convention. But she was the better journalist.

In its November/December 2001 issue, CJR ran a piece by Nick Spangler, a Columbia Journalism School student who was a few blocks from the World Trade Center on the morning of September 11. (He’s now a reporter at Newsday.) Its title is “Witness,” and, as with Altgens, there’s a lot that Spangler can testify to, including the sound of a blond woman in a sea-green skirt striking the ground. (“I could not see her face. I would not say I wanted to see it but I thought it was important.”) Much of the story, though, is about Spangler’s search, through clouds of dust, for members of the public who have seen more than he has.

Lippmann, in his conversation with journalism students, was skeptical of the public’s ability to handle complexity. One hopes he wasn’t completely correct about that. But he appeared to have a deep faith in the public’s ability to, as he put it, “say yes or no.” And, on a key concern of that period, the war in Vietnam—the reason protesters had gathered in Chicago—Lippmann identified how trust is ultimately tested: “Public relations was unable to do anything about the Vietnam War,” he said. “They tried to. Johnson tried all the techniques he could to hide that war, and then to make it acceptable. And it didn’t work.” When you know, in other words, you know.

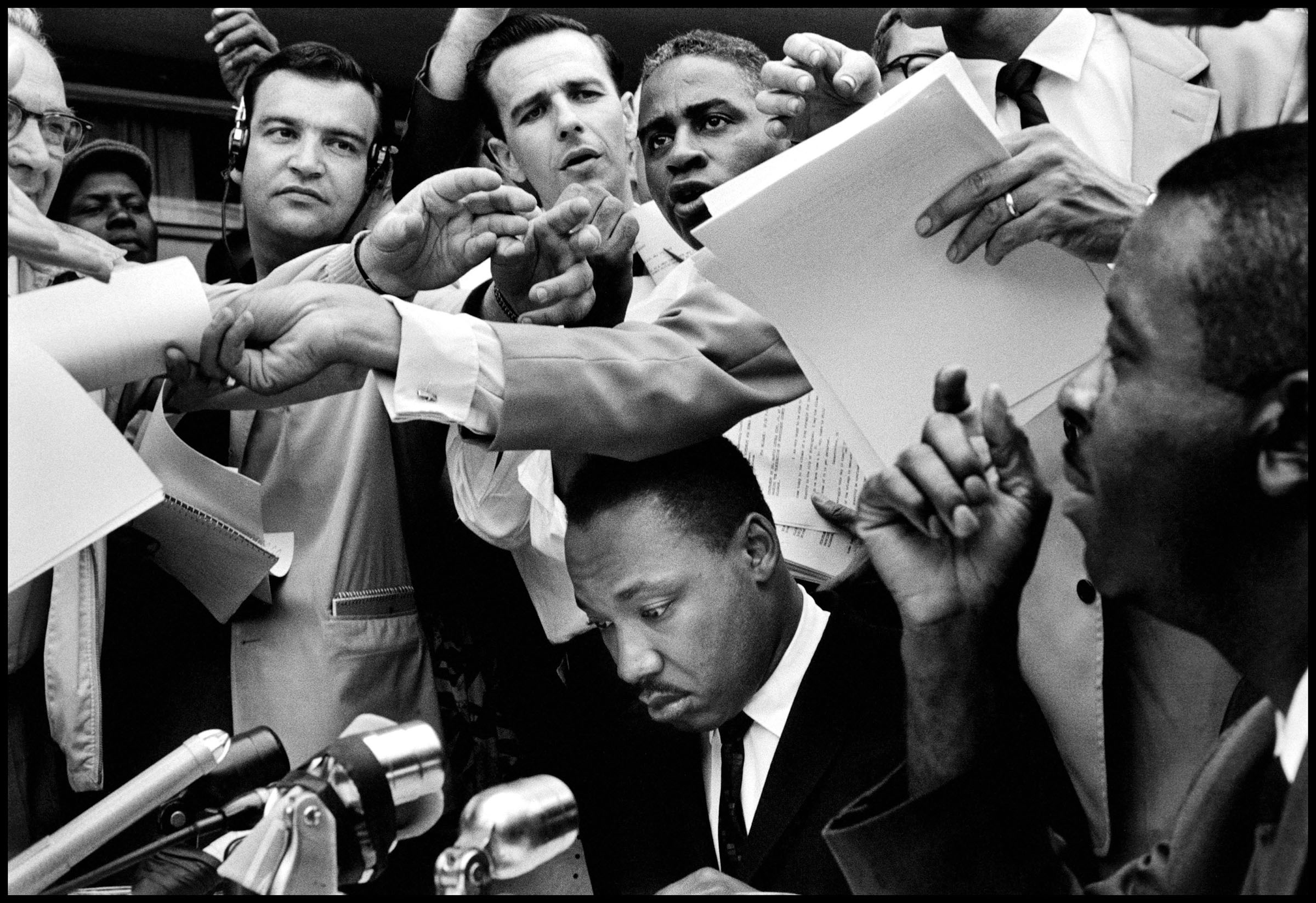

TOP IMAGE: Martin Luther King, Jr. in Birmingham, 1963; Bruce Davidson/Magnum