The Chicago Reader fired Executive Editor Mark Konkol on Saturday night, 17 days into his tenure.

The news was announced in a statement from Chicago Sun-Times and Reader CEO Edwin Eisendrath. “Mark came to the publication bringing great hope for a new direction and a new life to a storied brand,” Eisendrath said. “Sometimes things don’t work out as planned.”

ICYMI: One of the most dangerous jobs in journalism is one you might not expect

Konkol, 44, a Pulitzer Prize–winning journalist, pledged to bring “a new vibe” to the alt-weekly when Eisendrath hired him on January 31. Instead, he developed a reputation for being “a bully and a tyrant” inside the newsroom. He fired Editor-in-Chief Jake Malooley via phone after Malooley touched down at O’Hare International Airport returning from his honeymoon. Music Editor Philip Montoro alleged that Konkol “shouted me down in meetings, berated me, insulted me, and disrespected and alienated longtime freelance contributors.” (Konkol didn’t return texts or calls for comment on CJR’s story.)

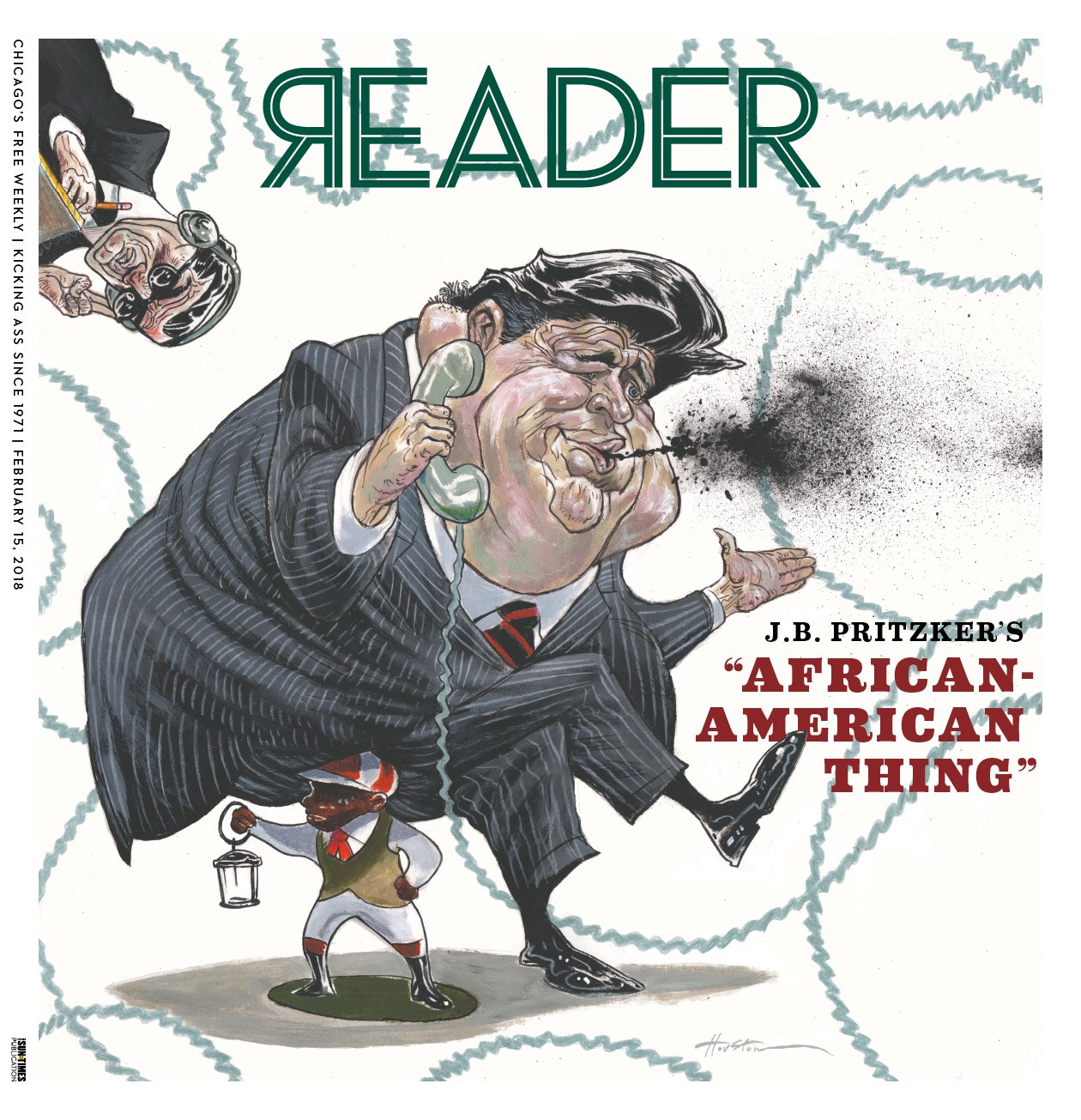

But what ultimately got Konkol fired was the political cartoon he put on the cover of the first issue he oversaw, which was anchored by my two columns about race politics. The cartoon depicts a particularly unflattering caricature of Illinois gubernatorial candidate and Hyatt heir J.B. Pritzker sitting atop a black lawn jockey, on the phone as an FBI agent listens through a wiretap.

The cover of the Chicago Reader, February 15, 2018 edition.

Reaction to the cartoon was swift and negative, and I was one of the loudest voices who cried racism, in part because a piece I wrote was among those illustrated by the cover. When I look at that cover it feels like I’m that red-lipped lawn jockey and Konkol is the powerful white man on my back.

“And you’re his new columnist?”

I worked with Konkol during stints at the Sun-Times, which owns the Reader, and later at DNAinfo Chicago. I’ve known Konkol since 2011. He and I were always friendly, and although I found him a bit callous he was usually pretty nice to me. He always told me I had a lot of untapped potential as a writer, and encouraged me. Shortly after Konkol took over at the Reader he called me and said he wanted me to be one of the new voices at the paper. My first column lampooned Pritzker for the coded racial language and tone he used in a leaked November 2008 conversation with now-jailed former Governor Rod Blagojevich about “the least offensive” African-American politician qualified for an appointment to the US Senate Seat vacated by Barack Obama when he was elected to the White House.

Konkol told me I had just written “a masterpiece” after reading the story. I ended my story on a personal and provocative note, noting how the smug and mocking tone of the Pritzker call made me feel as if one of them was going to laugh at any moment and say, “you know how niggers are.”

ICYMI: A journalist is approached by a man. He fires a pistol and she collapses.

But on February 9 at about 3:20pm, as Konkol was putting finishing touches on the piece, I watched in horror as he deleted the headline I had written in our shared Google doc, “J.B. Pritzker’s ‘African American Thing.’” He replaced my headline with, “Uncoding J.B. Pritzker: He Wanted A Nigger Democrats Could Control.” Konkol changed that to “Uncoding J.B. Pritzker: He Wanted A Nigger In the U.S. Senate The Democratic Machine Could Control.” Finally, he landed on “Uncoding J.B. Pritzker: He Wanted The ‘Least Offensive’ Nigger In the U.S. Senate.”

At 3:48pm, I left a comment that read: “I’m not into it, I’m sorry. Saying African-American isn’t as strong I know but I’m not down with this. It doesn’t feel right.”

Konkol called to try to convince me the headline would be a home run, that though my piece was excellent the headline needed to hit people like a punch in the face. I wasn’t moved. He gave me some time to think about it. Instead, I reached out to several local black journalists for advice.

First was my girlfriend, whose house I was typing at that day. She’s a TV and film critic for a New York-based legacy publication, and gave me a quick, “Hell no.”

Next, I texted a former Ebony magazine editor who serves as a mentor and confidant to other young black journalists I know in Chicago.

“That headline is loaded…it may also bring unwanted heat to the Reader,” she replied.

I texted another media professional who works as a writer and comic in Chicago.

“That does not feel right at all. That is clickbait,” she said.

I copied the text I sent her and sent it to a close friend who helps run a nonprofit newsroom on the South Side.

“Oh my f******* God,” he replied. “WTF…and you’re his new columnist?”

So I texted Konkol a few minutes later: “I’m not into it I’m sorry. It doesn’t feel right. We have to find something else. It feels click baity and it feels inappropriate and it’s not me. I’m sorry.”

But Konkol wouldn’t let it go. He called me again, this time dragging the Sun-Times into it, which owns the Reader and shares an office with it. He gave me the impression that a Sun-Times editor thought the headline was fine. When I pointed out that the editor was white, like Konkol and most of the newsroom, and re-asserted my dissent, he challenged me to think of a better headline if I didn’t like his. But minutes later Konkol called me again. He said I was on speaker phone, and introduced me to a cub reporter he had pulled from the Sun-Times, and whom I happened to already know.

She was a young black woman who Konkol thought might convince me the headline was okay, but once I explained my objection to her she was on my side. Konkol, sounding flustered and a bit angry, ended the call but told me once again to think of a better headline—and soon—because it was early evening at this point.

Konkol texted me after we got off the phone, “What about some reference to slavery? Uncle Tom? House slave?”

I ignored the texts.

Soon after the call, the young journalist messaged me on Twitter to apologize. “It’s cool,” I typed, “I’m just slightly frightened by all this haha it’s tough being a black writer I guess?”

She replied, “Yeah, me too. It’s definitely unsettling.”

At this point it was nearly 5pm. About two hours had passed since Konkol first pressed his headline idea on me. I sent him an email with a slate of potential headlines, and added, “These aren’t perfect but hopefully they can help the brainstorm?” And then I called him.

Our next conversation lasted about 16 minutes, according to my call log. Konkol pressed me harder than before to use the headline. He made it seem like I was selling myself short and being too timid, and told me to trust him.

I told him that I saw myself as accountable to the African-American community, and that I feared backlash from my people. I told him the headline felt cheap. I believed the merits of my piece should stand on their own, and that such a sensationalist headline would undercut it. I told him that he was making me uncomfortable given our dynamic. Here I was, a black writer, being pressured by a white editor at a white publication to use a hate-filled word in a headline. It felt like I was being exploited as a black voice and coerced to race bait.

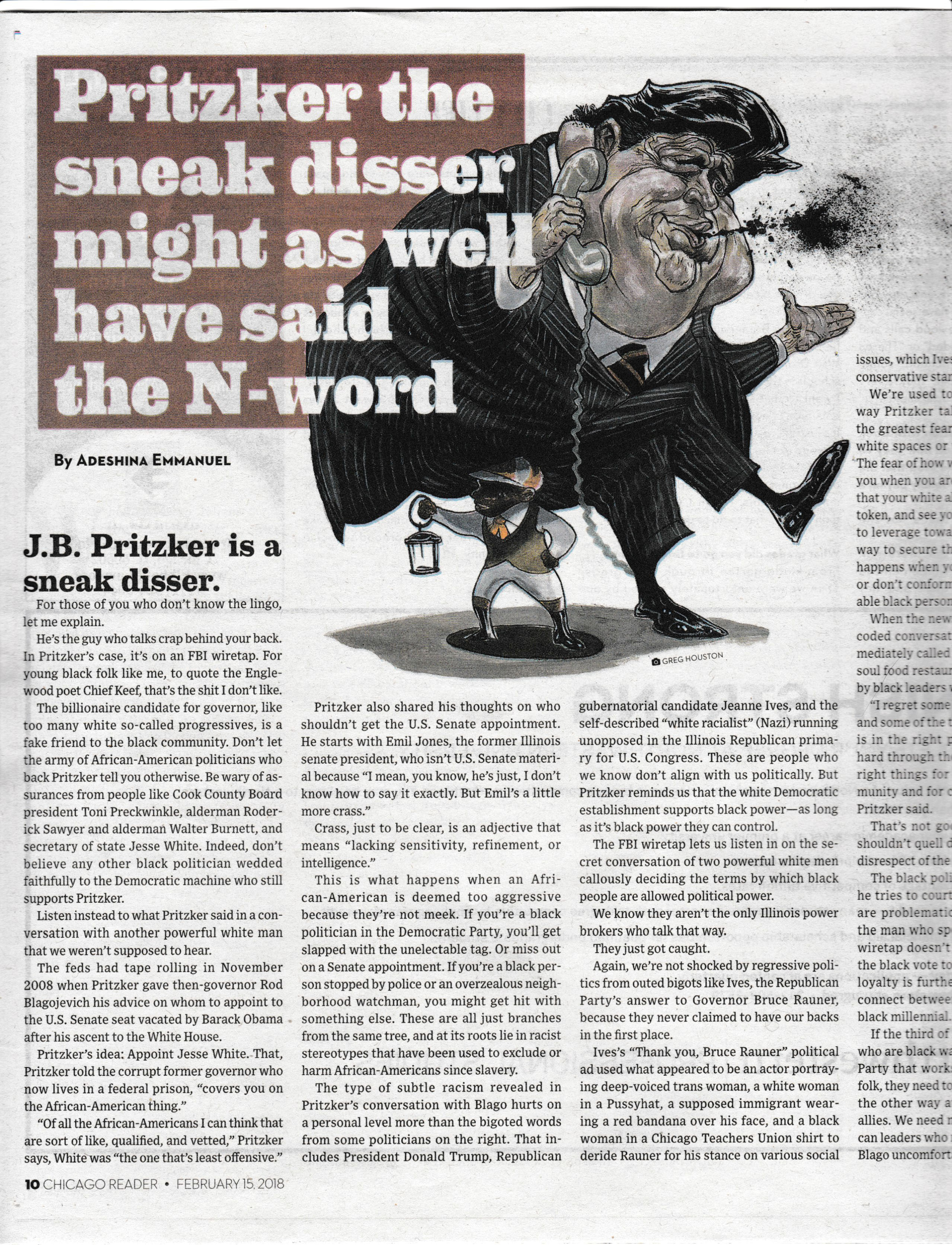

Once I mentioned my discomfort, Konkol grew defensive and even a bit sad because of the implications of what I was saying. He backed off, finally, and settled on this headline: “Pritzker, the sneak disser, might as well have said the n-word.”

My story was published online to generally favorable reviews. I watched on Facebook and Twitter as praise from my peers and audience poured in. Of course, everybody didn’t agree with me and I ruffled some feathers. But I was proud of my work.

My second column, published last Wednesday, addressed the black generational divide in politics, and the unequal partnership that old-guard African-American leaders and voters have with the Democratic Party, which depends on them to put white politicians in power but doesn’t always follow through with promises to the black community. There weren’t any headline issues like with my first column.

Taking a stand

Last Thursday, I awoke to see an article by Konkol on the Reader website titled “Pritzker’s ‘African American Thing’”—one of my suggested titles—with an image of the cartoon, which was to be the front cover of the Reader for a package on Pritzker including my stories. I texted Konkol and told him I wasn’t a fan of the cartoon.

Adeshina Emmanuel’s column as it ran in print.

“A fat white guy sitting on a lawn jockey eh? That will get an interesting response.”

“Good cartoon. Satire. Political commentary,” he replied.

I told him it was hard to see who was the actual target of the satire.

“Some people will see it as actually targeting blacks, not Pritzker or Democratic politics. The black JB supporter or black race reduced to a racially charged inhuman figurine. It sort of screams ‘Uncle Tom!’ It will grab attention certainly,” I texted him.

“Race is an uncomfortable issue,” was his response.

ICYMI: The New Yorker publishes a salacious Trump scoop

As I read through our text messages I realize I backed into my criticism, saying the artwork was good, and the explanation behind it was valid. I even texted him, “I’m not that bothered.” It hurts to type those words now. I’m somebody known among friends—and followers—for calling out racism.

Later that night, I had more conversations with several black journalists in my network and other journalists in the freelance and alt-media scenes who echoed my concerns about the cartoon. Multiple sources inside the Sun-Times and Reader told me Konkol’s original idea for the cover: J.B. Pritzker in black face. When I told this to the close friend of mine who helps run the South Side newsroom, he encouraged me to take a stand. The next morning I found a copy of the Reader and turned to the page where my “sneak disser” article lived.

I saw the cartoon Konkol put on the front page was also printed atop my story with the headline—the headline he had wanted so adamantly to put the n-word in.

It clicked for me.

I knew I had to tell my story and be willing to burn whatever bridges I had with Konkol or the Reader.

I stand by the points made in the text of my @Chicago_Reader articles. But I HATE that cover. Here’s why: https://t.co/IWtBIVMVII pic.twitter.com/iZTLC5N6S9

— Adeshina Emmanuel (@Public_Ade) February 16, 2018

“If I had known my first articles in the Chicago Reader were going into an issue with a black lawn jockey on the front, I would have bailed,” I wrote in a Facebook post.

“Sure,” I wrote, “I’ll be getting a check, and I gained some followers, but was it worth the humiliation of having my work under that cover? Does that cover really serve my people? I believe my voice as a black millennial man was exploited, used to lend credibility to what ultimately is another example of the type of sneak racism my articles called out. I feel used. It hurts.”

Konkol was fired Saturday night after my post and a chorus of complaints from other local journalists, black politicians, and members of the public. But as I tweeted, things like that cover are increasingly likely to happen in settings where there are not black people participating in editorial and production processes who can flag them. Things like what happened to me will continue to happen as long as vulnerable black writers are seen as commodities to gain approval from an underserved black audience.

In my Facebook post I cautioned other writers of color to protect their voices, and to learn from what happened to me.

I hope they do. I don’t want any writer to have to feel how I felt.

ICYMI: Fox News’s strategy for combating the Mueller Russia investigation

Adeshina Emmanuel is a Chicago-based journalist focused on race, class, inequality, social problems, and solutions who has been published in The New York Times, Ebony, Chicago Magazine, and by ATTN.com. He's a former reporter at the Chicago Reporter, Chicago Sun-Times, and DNAinfo Chicago. Follow him on Twitter @Public_Ade.