A companion study offering an overview of projects that attempt to tackle the challenges of polarization and sectarian divisions can be read here.

Executive Summary

Distrust in the “mainstream media” is now a central tenet of American conservatism, and this skepticism has consequences: Democrats and Republicans report vastly different understandings of matters of crucial importance, from the seriousness of COVID-19 and attitudes toward vaccines to the integrity of the 2020 presidential election.1 A society needs some shared set of facts and mutually trusted sources of information to function. In the U.S., we don’t have them.

While we know that there is pervasive distrust of news media among American conservatives—survey-based research has established it time and again2—we know less about the precise nature of the sentiment. How do conservatives interpret mainstream news? How do they explain their evaluations of news media and describe their feelings about engaging with it? To delve into these questions, we conducted 11 in-depth focus groups with 25 participants and conducted follow-up interviews with 16 of these participants. All interviews and focus groups took place from September 2020 to May 2021, with participants self-identified as conservatives who lived in Southeastern Pennsylvania or New Jersey. We focused these discussions on news coverage related to the COVID-19 pandemic, though we also addressed coverage of other major events taking place during that tumultuous time. Our approach to interviewing emphasized following up on moments when our interviewees expressed strong emotion or ambivalence.

What we observe contrasts with the two most prevalent models for understanding conservative alienation from mainstream journalism, which are that it is fueled by misinformation or fostered by insular media echo chambers. While there is plenty of evidence that misinformation can be powerful, we did not find the contesting of particular facts to be of primary importance to our interviewees. And though contact with conservative sources is important, most of our interviewees also report exposure to nonconservative media. Rather than isolation from mainstream media, the striking feature of our interviewees’ engagement with mainstream media was the interpretive framework they relied upon for making sense of it.

Overwhelmingly, our interviewees expressed suspicion of the institutional aims driving mainstream news organizations. Emotions ran high in talking about this perception.

Drawing on these stories about news organizations’ motives, our interviewees approach news through an interpretive filter that casts suspicion on the choices journalists make. This way of engaging with news is not just an individual disposition. Rather, our interviewees belong to networked interpretive communities linked to conservative media and conservative social media influencers. These networks construct narratives about news media that perform ongoing boundary work—placing news organizations in a category of liberal institutions at odds with the interests of participants’ communities. Individual news events are interpreted in ways that reinforce the broader argument: liberal media are trying to convince the world that American conservatives, and communities associated with conservatism, are morally defective. Journalists themselves are only incidentally a part of this story—interviewees’ explanations of who journalists are and why they do their jobs this way tended not to have a great deal of character development. The more salient point was that news organizations were dedicated to this purpose.

These dynamics fuel a powerful distrust. But our interviews also point to countervailing beliefs and attitudes. We found that interviewees largely shared a consistent story about news media and its problems only up to a certain level of detail. They initially shared criticisms of media that largely corresponded to talking points available in conservative media. But as we asked more probing questions, their responses appeared more unique and improvisational, and often signaled more ambivalence and uncertainty. Interviewer effects notwithstanding, in many instances, we found these more improvisational moments revealed attitudes that sat uncomfortably alongside the dominant framework of suspicion. These countervailing tendencies included sympathy for working journalists, admiration for certain moments of media coverage, and concerns about avoiding polarized echo chambers. These aspects of our interviews suggest the complexity of values and identities (e.g. conservative, mother, retail worker, citizen, etc.) our interviewees bring with them, and the variety of narrative resources they draw on, when they engage with news media.

There are two broad schools of thought about how contemporary journalists should approach conservative audiences: try to connect through strengthening commitments to professional standards of fairness or forget about them entirely. We argue that improving the relationship between conservatives and professional news organizations is not as simple as being attentive to conservative perspectives—but nor is it a pointless endeavor. We argue that efforts to engage cross-partisan audiences need to recognize that many conservatives’ relationships with mainstream media are themselves mediated through conservative outlets and social networks. Journalists can still serve democracy by providing vital information to cross-partisan audiences, if news organizations can find ways to confront the conservative filter head-on, and disrupt the stories it tells about the media and the identity boundaries these stories depend upon.

“So far gone”

Jake3was on the phone with an inmate when he first logged on for our interview. He apologized, explaining that he is a parole officer, and someone on his caseload had called just as he joined the Zoom meeting.

We settled down to business, talking about media coverage of the coronavirus pandemic. Like many of the conservatives we interviewed, Jake believed journalists had exaggerated the dangers of COVID-19 to embarrass Donald Trump. When we asked whether journalists were really so venal that they would manufacture a crisis and hurt the country intentionally, Jake took a firm stand.

“Yeah,” he said. “I think they are. I think they want anarchy.”

A bit later, we circled back to the subject of Jake’s day job. Jake, a middle-aged white man, explained that he supervises “a whole gamut of offenders,” from those convicted of DUIs to those convicted of murder, rape, and molesting children. For the most part, he felt he was able to cooperate with them, get them to see his point of view, and come to mutual understanding.

“I have very little problems,” Jake said. He attributed this to being empathetic—he told a story about choosing not to violate the parole of one woman who was caught stealing food, because “she probably needed that”—and to his ability to communicate in a way that guides and motivates parolees.

Hoping to build on this, we changed the subject back to journalism.

“What message can we bring to the journalistic community about how to connect better to conservatives?” we asked. “[Is there] a way you’d frame it using your skills from your profession to persuade them?”

Jake paused, and sighed.

“I don’t think you’re going to get that. I mean, I understand what you’re saying, but the journalists in this country are so far gone. It’s sort of like the teachers’ unions at this point.”

“Farther gone than rapists and murderers that you work with every day?” we asked.

For Jake, a reformed murderer appeared easier to imagine than a reformed journalist. “Let’s just say Trump’s reelected in 2024,” he said. “Do you think you’re going to start seeing positive news stories out of CNN? Or not even positive, but nonbiased news stories? MSNBC? They attacked him from before day one. And I just think that’s who they are. I mean, you just can’t change a leopard’s spots. A leopard’s a leopard.”

It’s probably not shocking to hear a conservative say he thinks poorly of the news media—distrusting journalists is a central tenet of American conservatism at this point. But Jake revealed two key things about the nature of that distrust in this conversation. First, that he regards the news media not merely as unreliable, sensationalistic, or biased, but as fundamentally and institutionally opposed to his interests. They’re not doing a bad job; they’re up to no good. Second, Jake is profoundly angry about this. He’s at a point where he can barely stand to watch even the weather on his local NBC affiliate, he says. When he reports in all apparent earnestness that he sees more hope for improvement in murderers and rapists than in journalists, it makes you wonder: How did we get here?

We conducted in-depth focus groups and interviews with conservatives to try to gain a deeper understanding of their relationship to the news media—not just whether they distrust journalists (which is well established), but how they explain and express their sentiments.4 Investigating the precise nature of conservative distrust of the media, and the social forces that drive it, could be crucial to counteracting it, which may in turn be crucial for the success of American society and democracy. We did this research during, and about, the COVID-19 pandemic, as clear an illustration as one could imagine of the need for a society to have some shared facts and mutually trusted sources of information.

What we learned contrasts with the two most prevalent models for understanding conservative alienation from mainstream journalism, which are that it is fueled either by misinformation or fostered by insular media echo chambers. While there is plenty of evidence that misinformation can be powerful, we did not find contesting particular facts to be of primary importance to our interviewees. And though conservative sources are influential, most of our interviewees also reported some exposure to mainstream news.

The key driving factor in how our interviewees think and feel about the news media, our research suggests, is an interpretive filter through which they understand both media coverage of individual stories and the motives of journalistic institutions more broadly. Seen through this filter, the news media present a threat to the dignity of conservatives’ identity. Interviewees saw journalists not first and foremost as professionals engaged in the collection and dissemination of information, but as part of a cultural power bloc dedicated to the advance of liberalism. Many conflated journalists with other categories of liberal elites, answering questions about news media with stories about, for example, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez.

In discussing this liberal power bloc, interviewees expressed anger not about its specific policy goals, but about what they saw as an effort to shame and ostracize conservatives. In the case of COVID-19, this meant that a great deal of news coverage was understood by conservatives to be aimed at blaming them (and the president they support) for the pandemic’s toll. Individual journalists themselves are only incidentally a part of this worldview—interviewees’ explanations of who journalists are and why they do their jobs this way tended not to have a great deal of character development. The more salient point was that news organizations were dedicated to this purpose.

This interpretive filter is, of course, not something people are born with. It is created and maintained by a networked interpretive community. Stanley Fish honed in on the concept of an interpretive community to describe how groups of people make sense of a text—or perhaps an event or experience—through a “set of community assumptions.”5 Fish, and the school of thought he represents, argues that texts don’t have fully fixed meanings in themselves; everyone draws on particular interpretive practices to make sense of them. So we are not saying conservatives are unique in having a filter for interpreting news media. It’s the nature of that filter that is unique.

Our interviewees were diverse in many ways, but they shared in common a relationship with conservative media sources and social media influencers who helped inform their interpretation of mainstream news. This interpretive community is not an “echo chamber.” There continues to be vigorous scholarly debate over to what extent a digital news sphere has led people to seal themselves off into like-minded enclaves or nudged them there through algorithmic recommendations.6 Interpretive communities can offer an alternative—or complementary—way to understand polarizing dynamics in media. Rather than being cut off from exposure to opposing perspectives, people like our interviewees encounter them regularly, usually as an ambient feature of their media environment. But they draw on their interpretive community for guidance and support in understanding what they see. This particular community provides an “oppositional” reading of mainstream journalism, anchored by the narrative that the media want conservatives “expunged from our society,” as one of our interviewees said.7

Whether the public shunning of conservatives is actually happening—or actually warranted—is beyond our scope. However, the social processes that encourage and reinforce the belief that ostracism is a central goal of liberalism are important to understand. Journalists who might wish to build more cross-partisan trust need to recognize that, while instances of liberal bias can enhance the credibility of the interpretive filter’s story, no amount of professionalism, evenhandedness, or even kowtowing to the conservative perspective is likely to meaningfully improve trust. The conservative commentators and influencers who ceaselessly revile the media are not, for the most part, focused on getting friendlier coverage of individual issues. They will tell their story about journalists being villains regardless of what journalists do, because the villain is the point of their story; the media is the message.

At the same time, journalists who are tempted to write off conservative audiences entirely, either because of perceived practical pointlessness or moral undeservedness, should know that there are holes in the interpretive filter. We found a deep suspicion of mainstream media among our interviewees, but they also expressed many of the same basic desires for democratic journalism one might hear from people of any political persuasion: a longing for a trustworthy media that respects audiences’ intellectual capacities and strives for fairness in presenting clashing perspectives. These longings point to opportunities for a different kind of relationship between journalists and cross-partisan audiences, one that could strengthen American society’s ability to address climate change, fight a pandemic, confront systemic inequalities, or hold free and fair elections. Pursuing these outcomes, we suggest, will require finding creative ways to break through the conservative filter.

Methodology

It’s become a cliché for writers to parachute into parts of the United States typically neglected by national media, interviewing white, rural, or exurban conservatives in diners and trying to discover a side of America invisible to urban elites. Such endeavors are sometimes cast as disrespectful—swooping in with a sneer or patronizing sympathy—and sometimes as too respectful, centering a politically over-represented group’s concerns rather than those of more marginalized groups who also often feel alienated from media institutions.

There is immense work to be done to develop deeper understandings of the relationships between news institutions and a wide array of marginalized and alienated social groups. Despite widespread concern about media polarization, little U.S.-based research has explored the specific practices of left or right partisan audiences.8 Our own research, of course, offers only a limited scope, but it is important to examine conservatives’ fraught relationship to professional news media right now, as this is a dynamic upon which the future of American democracy partly hinges. This can be done respectfully without being done credulously.

In this study, we focus on understanding our interviewees’ thoughts and feelings and the conditions shaping them.9We recognize that there are places where it’s important to debate how well these perceptions conform to reality (e.g., is COVID-19 really no worse than the seasonal flu?). But our task here is to capture them descriptively as best we can and try to illuminate the social processes that produce them.

To that end, we conducted in-depth interviews and focus groups with conservative news consumers from Southeastern Pennsylvania and New Jersey, with the aim of developing a nuanced understanding of conservatives’ engagement with news. We conducted 11 focus groups on Zoom with two or three participants in each group, with a total of 25 participants. Each session lasted about an hour and a half. We then asked participants whether they would meet again for follow-up interviews, and we spoke with 16 of them for interviews typically lasting an hour. Our focus groups took place from September 2020 to January 2021, and follow-up interviews from January to May 2021.

We used a semi-structured interview approach.10 Our initial questions explored interviewees’ emotional experiences with news, because we wanted to understand the emotional context in which they formed their thoughts (e.g., if someone said a certain type of news coverage upset them, we wanted to understand what perceptions made that coverage so upsetting). We listened for and pursued further inquiry when we heard ambivalence, tension, and heightened emotion in our interviewees’ stories. Our conversations began with a focus on COVID-19 news coverage, but expanded as we touched on media coverage of key events in this time period, including racial justice movements, the 2020 election, the Capitol insurrection on January 6, Donald Trump’s impeachment trial, and the first months of the Joe Biden administration. In this paper, we focus mostly on COVID-19.

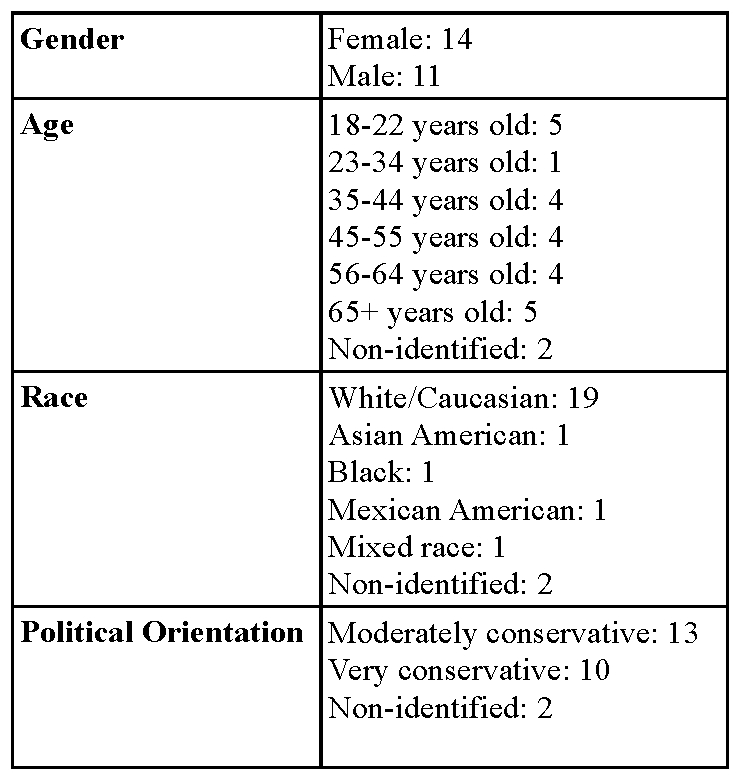

In recruiting participants for this study, we sought to hear from a diverse range of conservative voices across key demographic categories including race, age, gender, class and educational background, and ideology. But our sample is limited in racial diversity and certainly not representative of Philadelphia-area conservatives as a whole nor comprehensive of the variation among them. Nonetheless, the diversity of our participants’ backgrounds helps us understand conservatives’ interpretive practices across some of this demographic diversity. Our interviewees predominantly identified as white (76 percent) and ranged in age from young adults in college to a retiree who was 79. Interviewees included service workers, homemakers, sales agents, a welder, small-business owners, an executive, college students, and professionals from several fields. The self-identified demographics of our participants were:

Self-identified demographics of participants (Note: While we had two “non-identified” people in several categories, these were not the same two individuals in each case.)

What conservatives talk about when they talk about “The Media”

Tune in to any number of conservative voices and you will hear reference to the “mainstream media,” the “liberal media,” or just “the media,” made in tones suggesting that everyone listening knows exactly what the speakers mean and exactly what the media did wrong. But we didn’t know these things. In interviews, we invited our interviewees to talk about their specific media habits as well as the more general impressions they have of who the media are and what they do.

We began by asking our interviewees where they get their news. They described wide and varied media diets, ranging from social media to cable news to news sites to podcasts to push notifications. Almost everyone relied at least somewhat, and most relied heavily, on what we would describe as conservative sources, including Fox News, but also Newsmax, One America News Network, Epoch Times, Ben Shapiro, and Steven Crowder.

The great majority of our interviewees said they also valued encountering sources with different points of view. For several, this meant intentional efforts to scan nonconservative sources, especially through grazing headlines. A few told us they try to expose themselves to nonconservative media beyond headlines, but could find it frustrating.

Lily is an undergraduate who identifies as biracial. She told us, “Sometimes I watch CNN just to … get information from different viewpoints.” But she found, “I usually just get very irritated and I just have to go … like, click off it.” Most couldn’t describe specifics of regular engagement with particular sources outside of the right-wing media sphere, and some said they actively avoided such experiences. Nonetheless, all spoke confidently—and often quite forcefully—about what “mainstream media” were up to.11

Looking closely, we found that our interviewees described mainstream media as an ambient feature of their environment. Most didn’t make any “appointment” viewing of mainstream news programs or visit a particular newspaper site each day. But they did come across mainstream content in a variety of circumstances, including push notifications, web portals (especially Yahoo), links shared on social media, and clips of mainstream news replayed by conservative media or commented upon by conservative influencers. Phil, a white 79-year-old retiree, told us that while he sometimes tunes to CNN and MSNBC to see what’s going on at the “opposite end of the spectrum,” he often relies on “clips on FOX of what MSNBC and CNN have said. I get the impression to a certain extent based on what FOX is telling me was said on those networks and provides the actual clips.”12

So who is “the media”?

For another of our early questions, we asked interviewees to give “the media” a grade for their COVID-19 coverage. We’ll discuss their assessments below (spoiler: the media will be on academic probation). For now, we want to focus on the fact that most interviewees were able to answer this question without any explanation of who we were talking about, and when we followed up by asking who they were talking about—who constitutes “the media” to whom they awarded generally poor grades—they gave us a pretty consistent set of answers: CNN, MSNBC, network news, the New York Times, the Washington Post. The term “the media” initially coded quite clearly for our participants.

But as the interviews progressed, our interviewees consistently revealed an understanding of what or who constituted news media that, at first, confused us. We’d ask questions specifically

seeking their reactions to the news, and their responses often conflated journalists with other actors whom we saw as belonging to wholly different categories. They would weave in and out of talking about institutions such as academia or Hollywood, or talking about liberal politicians, as if they were representatives of mainstream media. Here’s how Phil described the overarching problems with news coverage of COVID:

There is a rabidly liberal Congresswoman who I think we all know named Alexandria Ocasio Cortez, a.k.a. AOC.

So this was a tweet on her account in May of this year, it’s a very short tweet. Okay. She says, and I quote, “It’s vital that governors maintain restrictions on businesses until after the November elections because economic recovery will help Trump be reelected. A few business closures or job losses is a small price to pay to be free from this presidency #KeepUsClosed.”

So I think that in a nutshell kind of sums up the left-leaning media’s position on this, to acknowledge that it’s a real thing, yes. But also, to blow this thing out of proportion in an exponential way for political purposes is why I don’t put too much trust into what I’m hearing on any given news channel or on the front page of any given newspaper.

This counterfeit tweet attributed to Ocasio-Cortez had been widely circulated in Facebook groups and other social media.13

But more than the uptake of misinformation, what we came to see as striking is the ease with which interviewees like Phil would conflate journalists with other characters.

As we became more aware of this pattern, we came to see it as a type of boundary work crucial to the interpretive filter our interviewees applied to news. The concept of boundary work comes from sociology to describe the social processes that produce what Michèle Lamont calls “the taken-for-granted categories” of social classification. People draw upon these categories for “interpreting and organizing the differences around them.”14 In assessing journalistic coverage of COVID-19, for example, we imagine that most journalists and researchers would consider a line between journalism and not-journalism to be a foundational distinction. Though our interviewees can surely draw conceptual distinctions between journalists/journalism outlets and other occupations and institutions when it matters to them, this was not always the most salient boundary for them. Instead, their responses suggest a map of a social world in which the distinctions that matter most lie not along an occupational dimension but instead separate powerful liberal institutions from their own communities.

Consequently, experiences and observations interviewees had about non-journalistic actors could end up defining their emotional responses to journalists. Consider this answer from Maria, a Mexican-American HR professional, in which she explains the problems with mainstream COVID-19 coverage:

If you look at the people who are at the top of these news organizations, they have their own political agendas. They are affiliated with their own parties, and so that’s the way that the news skews itself, and their actual stories are written not to inform people but are written to manipulate people. It’s absolute indoctrination. I mean, I’ve been in the classroom with a nun who wrote on the board literally in Los Angeles, California, “Republicans are evil,” and did that because she knew I was the only Republican in the classroom, and made this speech about why she was a liberal and how I should become a liberal. I just thought, this is absolutely wasted. That’s kind of the agenda there. It’s the indoctrination of intolerance and really just trying to get people to vote in different ways . . .

How did a nun teaching in a Catholic school in California become a representative of the news media? If mainstream news is seen as just one part of a liberal power bloc, the connection makes more sense. Maria draws on her experience with someone she views as representing authority in a liberal institution to make sense of mainstream journalism.

What did the Mainstream Media do to you?

When our interviewees think of “the news media,” then, they seem to think less about concepts like “the collection and dissemination of information” and more about concepts like “liberal” or “Democrat.”

This helps to explain some of the anger we see toward journalists from the right these days—many people dislike their political opposition. But our interviewees’ complaints about the media were not simply “We disagree with their ideas,” nor even “They are frauds pretending to be objective when they are not.” We heard only some of the latter and almost none of the former. Rather, time and again, interviewees pointed to what they saw as the demonization and attempted ostracization of conservatives—and the effects of such efforts they said they felt in their own lives—as the media’s true and unforgivable sin.

Tim, a white college student who had worn a red “Make America Great Again” hat to his first, pre-election Zoom meeting with us, told us in a post-election interview that he was disappointed by polls showing that many conservatives believed President Trump’s claims that the 2020 election was stolen. He thought this was delusional. But, he said, this was understandable given what it feels like to be a conservative today: “The feeling that conservatives usually have which is, when you have every cultural outlet in your life stacked against you or at least leaning against you.” He listed examples from his own life: he couldn’t express his political views at work for fears of retribution, faced shaming in his classes at college, and witnessed artists and entertainers “cancelled” if they expressed conservative sympathies. He charged that “an echo chamber in the media, in Hollywood, in college” had fomented a hostility toward conservatives. “We’re basically seen now as the outcasts, the savages, which is pretty hyperbolic language, but honestly, there are a lot of people who do see us as savages.”

Arnie, a white manager of a team of service workers, recalled with some anger that in a “rant” after the January 6 insurrection, Keith Olbermann argued that “all Trump supporters and those around him need to be expunged from our society.” He offered this as a representative example of the media’s attitude toward conservatives. The narrative liberals wished to tell the country, he said, was that “every conservative is a Trump supporter, and every conservative needs to be put in a box and never heard from again because everything they’re going to say is in support of somebody who incited an insurrection.”

Many interviewees told us about personal relationships that had been strained or even ruptured under partisan duress. They attributed these difficulties to liberal intolerance, fueled at least partly by the news media and other liberal institutions vilifying conservatives. Mary, a white retiree in the Philadelphia suburbs, got along well with her son, she said, but they still had unpleasant political disagreements. She said she knew that such disputes sometimes break families apart. “We paid for an expensive education at [university name removed], and I knew they were going to turn him into an atheist and a communist there, and they did. It’s kind of our own fault for sending him there. But no, I understand other people have that problem with their families. … You send your child away to college, and they turn them into people who hate their parents. It’s not nice.”

Chloe, a white realtor who described herself as a “millennial conservative”, said political disagreement had caused old friends to unfollow her on Facebook. “When I get going, politically, on my Facebook, I’m like, ‘Here I go, I’m calculating 10 by the end of the day.’ I have, of course, probably lost two dozen to maybe three dozen people that I’ve known since childhood off of, basically, my conservative political beliefs.” The level of “tolerance” she felt from liberals, she said, “has definitely dwindled … I’m just seeing, ‘Okay, I’m just done with dealing with people like you.’ Before, you’d have a debate or some lively discussion and that would be the end of it, and now it’s just, ‘Okay, I don’t want to hear your shit anymore.’”

Our research design doesn’t allow us to make objective judgments about whether these perceptions of ostracism are rooted in reality—or assess any justifications for such ostracism. What we can offer is an analysis of how our interviewees make meaning and the emotional lenses through which they engage with the media they blame for this threat of ostracism, while seeking insight into how their interpretive practices inform responses to important issues and events covered in the news. Including, for example, COVID-19.

Making Sense of COVID-19 Coverage

It would be hard to think of a better example of a situation in which a society needs shared, trusted sources of information than a pandemic, during which survival depends on collective measures. To hear our interviewees tell it, a key reason the United States did not achieve a sense of mutual purpose was that the mainstream media were so transparently biased and irresponsible.

Our discussions with interviewees sought both general impressions and responses to specific examples of media coverage. All of these were shot through with the same sense of suspicion that the media’s central purpose was not to disseminate useful information, but rather to exploit the pandemic for commercial and political gain by exaggerating its scope and blaming and shaming conservatives for their response to it.

To be clear, the issue was not that interviewees dismissed the threat COVID-19 posed. We heard a range of perspectives on how seriously the disease should be taken. A few participants suggested it is comparable to the seasonal flu, but that was not the most common view. What we heard most frequently was that COVID-19 poses serious health threats, but that media and liberal politicians obscured the degree to which those threats were largely limited to specific vulnerable groups, namely the elderly and those with certain pre-existing health conditions. This conception dovetailed with some of the criticisms we heard of liberal policy responses to COVID-19. Many interviewees said public health mandates like lockdowns and mask requirements needlessly affected everyone when measures tailored to protect only those at greatest risk would have been best.

Whether or not one respects this assessment, it’s important to understand the positioning. Most of our interviewees viewed themselves as reasonable and moderate in their orientation toward the pandemic. It was the news media, they said, that misrepresented conservatives as extreme denialists, as part of a larger project to distort reality.

Just the Facts, Please

Interviewees were overwhelmingly clear about what they wanted from journalists regarding COVID-19: “Just the facts.” This stated desire is, of course, not limited to conservatives, and raises as many questions as it answers. Which facts? Arranged in what order? Should officials be quoted? Should their claims be questioned?

It’s perhaps too easy for scholars to read “just the facts” as either a naive fantasy of the impossible or an egocentric fantasy of one’s own interpretation of truth going unchallenged. Our interviewees, however, demonstrated that they understood some of the related complications. Several who said they “just want facts” would acknowledge that values go into selecting which facts to prioritize. For instance, when we asked interviewees to comment on an infographic from the website of the Philadelphia Inquirer that depicted the number of confirmed COVID-19 cases and deaths in different counties, many said they thought the infographic conveyed a bias. Arnie told us:

Well, the wrinkle is, that as my father once put it when I was a young man, figures don’t lie, but liars figure. The statistics are what they are, and anybody can put together damned lies and statistics. So the numbers are what they are. You know you have X number of hundreds of thousands of deaths. You have X number of millions of cases of infection. Those are facts, irrespective of the source of those facts, they’re facts. And you can’t ignore them. So it’s not that part of the narrative that bothers me, but it’s the incessant positioning of that number as something negative, as something egregious.

Other interviewees echoed Arnie’s argument that journalists were not offering the proper context to understand the significance of COVID-19 deaths and cases. Tim told us, “A lot of gripes that conservatives were having was [sic] that if you look at these media sites, they would always have a little ticker tape showing global deaths and US deaths.” Though he didn’t dispute the factual status of death records, he said, “the purpose of that ticker tape—there isn’t really a purpose other than to scare people because they see this giant number, and they’re going to be scared of it.” Several interviewees insisted that the media should put more emphasis on mortality rates by age, like Frank, a white executive and father, who told us, “Those statistics are what’s important to me, but unless you search for that, unless you specifically look for that information, nobody is talking about that in mainstream media.”

When we pushed for a more specific explanation of how to implement a “just the facts” approach, given these challenges, we didn’t get entirely coherent visions. But the inconsistencies themselves tell a story. Jennifer, an Asian American homemaker, has served on a local committee for the Republican Party and is involved in her local community. She offered a revealing characterization of what she wants from journalism that may have more significance than a slip of the tongue. “The role of a journalist is not to tell me what to think and what to believe,” she said. “The role of the journalist is to put out unbiased opinion. I’m sorry—not opinion; unbiased facts from both sides.” The idea that facts could come from “both sides” yet be unbiased points to one of the contradictions we heard a number of interviewees grapple with as we pushed them to elaborate on what “just the facts” could mean.

Looking really closely at what interviewees say they want from “just the facts” news, we hear a longing for a sense of intellectual autonomy and respect. Again and again, we heard interviewees say that they resented journalists for telling them “what to think” and not treating them like adults who could exercise their own judgment.

COVID Coverage and the Question of Blame

The most frequent, most passionate complaint we heard about COVID-19 coverage was that journalists slanted it to make conservatives in general, and Donald Trump in particular, appear at fault for the virus’ toll. This was the organizing principle they saw at work in the selection and prioritization of facts, and the narrative they saw constantly pushed. “The only real fact I’m hearing from them is the death toll,” said Benji, a white undergraduate student, “and then they go off on how bad Trump is. … I mean, they want to think this is all Trump’s fault? Go for it. But I don’t think that’s the message the media should be sending out. I think it should be objective.”

Questions of blame and guilt around COVID-19 deaths could stir emotional responses. Alesandro holds a Ph.D. and is currently an adjunct instructor while on the job market. He said that watching how the mainstream press treated Trump during press conferences made him feel they “were out for blood from the beginning,” trying to pin all the suffering caused by COVID-19 on Trump and his supporters. At times, it was hard not to hear a defensive note, particularly among more committed partisans who seemed to be grasping for justifications to absolve their side from blame. Stella, a white retiree, gave voice to her frustration:

All I want is the truth. I just want a factual truth. I don’t want this mass hysteria. I don’t want the blame game, because what they’re doing is actually laying guilt on certain people for something that may not have been naturally occurring, by the way, but the blame, it’s not what you call it. It’s where it’s from. It should be truthful in saying there’s no denying the origin of this virus. No one’s denying it now, but they want to call it different things.

Stella disavows the “blame game, but” then implies China should be blamed for COVID-19. She goes on to say that blame might appropriately be apportioned to other parties, including local government officials for botching responses in nursing homes and correctional facilities.

Indeed, a number of interviewees struggled to find a coherent response to questions of blame. Some, like Stella, seemed torn between wanting to say media were too focused on who was at fault, and that liberals and Democrats had screwed everything up.

We looked for creative ways to broach the subject. One approach we tried was to ask for responses to a clip from Tucker Carlson Tonight from March 26, 2020, in which Carlson blamed Democratic politicians for contributing to COVID-19 deaths in New York City by exhorting people not to succumb to racist fears of the virus and go out and ride the subway and celebrate the Chinese New Year. We wanted to see if interviewees would speak with more ease if the question of blame was directed toward Democrats. But even this question could trigger a defensive posture. Here’s how the tension played out in one of these conversations:

Interviewer: I want to ask your thoughts of the argument that Carlson’s making there. Do you think that there were liberal Democrat politicians who were encouraging people to go out at the time and suggesting that racism might be to blame for fears about the coronavirus? Do you think that they hold any blame for the deaths that happened in New York in March?

Phil: Okay. Here’s the problem. Everybody wants to say Trump didn’t do enough. Trump was … trying to figure out what was going on. … Before I can really accurately answer it, I have to see what Trump’s position was. Say one or two weeks, what the press conferences were saying, or what was going on now. Now you have the reporting by [Bob] Woodward, where Trump potentially was trying to downplay the virus so as not to panic the people, and I think he was genuinely trying to figure out what was going on. It depends. … It’s a really hard question to answer, [Interviewer’s Name], because it depends on how much information those New York people had to make that decision to do what they did.

Phil immediately jumps from Carlson’s claim about Democrats to a defense against blaming Trump. He was cautious in assessing Carlson’s argument explicitly because he didn’t want his reasoning to be able to be used to justify culpability on Trump’s part.

Fearmongering as a Commercial and Political Strategy

The news is too scary—that was the other major complaint we heard from interviewees about COVID coverage. “I think the fearmongering is coming to a breaking point,” said Xander, a 20-year-old white college student. He complained, “Every time I turn on the news, it’s ‘breaking news.’” Chloe described watching the news as “being fed death and destruction,” and saw this as a choice news outlets were making rather than a reality dictated by the pandemic itself. As she put it,

I mean we have one of the local hospitals, Pottstown, recording people leaving the hospital with parades of people, “Yay, we beat COVID.” You don’t see that. They’re showing you the body bags, as they’re getting ready to go bury the people in the mass grave up in New York. … I keep going back to my mother-in-law. She’s 80, and she’s at home. She’s scared. She can’t breathe.

Interviewees spoke of fearmongering as both a commercial and political strategy, not always drawing clear distinctions between the two. It was understood to drive both ratings and opinions. Maria told us she thinks fear is the media’s “whole objective, and usually fear is what causes people to react emotionally, and then make, in my opinion, irrational decisions because you’re not clear-minded.”

Other interviewees said the media only displayed concern with COVID-19 when doing so reinforced dominant liberal narratives. Several complained about transmission fears evaporating during the protests in the summer of 2020. As Samantha, a white university instructor, put it, “When we have the riots that were occurring, we had those groups that were not wearing masks, and again that wasn’t exactly emphasized as a negative, but when you have pool parties or people at beaches who weren’t wearing masks, it was completely overdramatized and made into this negative concept.”

She also emphasized her own experience of what she felt was a double standard. “George Floyd had four mass-attended funerals … my grandfather passed away in April right after the pandemic and we still have not buried him. It’s heartbreaking. My grandma had to say goodbye to her husband of 66 years over FaceTime because he was in a home and she’s still at their house.” In her interpretation, the media had hyped fears of COVID-19, leading to lockdowns. Furthermore, she suggested journalists had pushed an insulting narrative that minimized the sacrifices people like her had made in the pandemic.

Interviewees offered a range of ideas about the precise political purpose of fearmongering. Some said it was part of a general zeitgeist associating conservatives with COVID; others saw something more sinister, thinking COVID-19 fears could be used as a pretext for left-wing authoritarian measures. Most contended that fears of the virus were inflated specifically to hurt the prospects of Donald Trump and other Republicans in the 2020 election.

In a few of the interviews we conducted after Joe Biden’s inauguration, we tried asking some of the people who made this argument whether and why the media had continued to sound the alarm about COVID-19 with similar fervor, if the purpose had been served. Arnie conceded that coverage hadn’t changed much, and expressed bafflement as to why:

I wish I knew. That’s the ultimate question I don’t have an answer for. There’s no reason that I can see, statistically, legitimately, factually, for keeping up that narrative now. Even from an emotional perspective. The only thing that I can see, and this is conjecture, this is not fact. This is conjecture. The only thing I can see is that they need to back up a new narrative of capitulation, conformity. Do it our way because we say so, and don’t look into anything. There’s no other reason for it at this point.

Part of exaggerating the threat of COVID, interviewees said, was underplaying key parts of the story, including the economic impacts of lockdown measures and the curtailment of civil liberties. In some of our pre-election interviews, several interviewees said the press was ignoring the phenomenally good news of vaccine

development. Openness and Curiosity Beyond the Filter

When we asked participants to grade media coverage of COVID-19, most said the media’s final grade was a D or an F. Interestingly, though, several participants specified that the initial coverage of the pandemic was better. At the very start, when “no one knew anything,” Samantha recalled appropriate, helpful news coverage.

I think the first two to four weeks of the lockdown, I would have given them an A. … We didn’t know really where it came from. That was kind of unsure. We didn’t really know how contagious it was, so they were saying wipe your groceries, wipe your mail. That was all great because we didn’t know. But I would say that covers the first two to four weeks. After that, we started having more information, and they didn’t change their narrative.

Maria echoed this sentiment, saying that coverage was much better before journalists really started focusing on the Trump administration’s response:

I think they were more educational during that period rather than blaming, and it really progressed moving forward especially closer to the election that it became a Trump issue.

When the coverage did turn sour, interviewees told us, they did not simply turn to conservative sources. A few of the most hardened partisans said they checked the Epoch Times for what they considered to be the real facts. But for more, while they were invested in avoiding outlets that cast conservatives in a negative light, they generally did not express faith in information sources like President Trump or Fox News. They described searching for sources without political agendas.

Several interviewees told us they relied on doctors they knew for advice. Others said they turned to public health agencies. Phil, who expressed great disdain for media fearmongering, told us the “CDC website is an invaluable resource for just straight data,” and also turned to the website for the American Association of Pediatrics. Among those in our sample, we found college-educated conservatives, in particular, looking for sources they saw as both politically neutral and well-credentialed in medical or scientific expertise. Whether this pattern would hold for a larger population would require further research.

We also found that many of our interviewees spoke of moments when they were unsure of how to assess the threat posed by COVID-19 and sought information from sources they thought would not be tainted by any political bias. Some questioned sources or rumors popular on the right that downplayed COVID-19’s significance. In one focus group, after a participant raised suspicions about whether hospitals might have inflated deaths from the virus or lied about early shortages of personal protective equipment, Alesandro said he had entertained these thoughts himself, but pushed back with a story from his brother, a scientist who had been able to bring some needed PPE to a doctor friend. Alesandro described what he learned:

And so, [his brother’s friend] came to pick [the PPE] up and he said the guy was in shambles. He’s crying, he’s saying he’s got people dying in his arms left and right. And so it’s like, okay, you get that piece of info, which is perfect. It’s from an actual person. I’m not relying on a source that might be biased; it’s someone that I know, it’s a friend. That kind of info was gold for someone like me. So, okay, that tells me, yes, there is clearly something going on in the hospitals.

We heard this sort of sincere-sounding curiosity about the truth of COVID-19 from many interviewees. Still, the emotional valences here are noteworthy. Alesandro expressed no anger at those who claimed COVID-19 was not really causing a crisis at hospitals.

Time and again, when interviewees pushed back against narratives or conspiracies popular among conservatives, they did not express the level of anger or frustration they voiced when finding fault with narratives or institutions coded as liberal. In talking about the large numbers of people in nursing homes who had died in her area, Joan, a white retired medical professional, told us, “Now, some people’s theory is that the far left want the old people to die, because they’re useless, and they’re costing too much money.” However, she said, “that’s just a radical thought. I mean, I just can’t believe that that would be happening.” Still, she said she could understand the feeling of not being valued or respected that led her older, conservative friends to entertain such thoughts.

What Motivates Journalists?

When we began this project, one of our hopes was to engage our interviewees in thinking and talking about journalists not as an abstract class, but as real people. As we conducted initial focus groups, we began to realize that one promising way into this subject was through coverage of COVID-19, which provoked deeply cynical explanations of press rhetoric.

We have good news, bad news, and interesting news for journalists who would like to think people like our interviewees might offer them some generosity.

Recall Jake the parole officer, who could find hope for salvageability in rapists and murderers, but not in journalists. The good news is that this was not a typical viewpoint. Only Jake and a few others seemed to have reached this deep a stage of alienation. Most had not decided that Wolf Blitzer is a Generic Doomsday Villain. They attributed complex motivations and attributes to journalists. The bad news is that the more nuanced explanations of journalists’ motivations we heard from most interviewees were not necessarily flattering. The interesting news is that the conservative interpretive network writ large seems not to have settled on a clear or consistent theory of the case for why journalists do what they do. Unlike with subjects such as the quality of COVID coverage, about which we heard the same coherent storyline from many interviewees—often a storyline we could trace back to conservative media—answers to our questions about journalists’ motivations were various, and seemed improvised, unconfident, and even confused.

The story a fair number of interviewees told about journalists is a tragedy that begins with promise. “I think that people get into journalism, they’re well intentioned,” said Chloe. “I would like to think that somebody who is going into journalism is doing it from a place of wanting to inform and help people,” said Maria. “I think a person that goes into journalism would be a truth-seeking type of person,” said Samantha. “I’d like to think that journalists start off … from a humanitarian perspective, they want to help people, bring the right news to the world, be on the ground reporting, bringing truth to the world, all of that.”

These comments offer two striking insights. The first is that these interviewees don’t think reporters went into the field of journalism with the intention of misleading people, the way some people might say a Wall Street executive went into his field simply out of greed.

The second observation is that the positive values and intentions the interviewees ascribe to journalists are consistent with values you might find at the heart of a journalist’s creed: truth-seeking, informing, and humanitarianism. While there is evidence of tensions between some Americans’ core values and journalistic values,15there is some shared understanding about the bedrock purposes of the profession.

One possible explanation for this diversion from the general conservative narrative around the press is that the conservative interpretive network hasn’t actually done much to address the question of who journalists are and why they go into the work, leaving our interviewees to draw on other cultural resources to fill in these narratives. And so they rely on the story journalists tell about journalism, or ask why anyone might go into a field. A common such story in our culture is a story about ideals. One interviewee even analogized a journalist entering the profession to her own decision to go into human resources to help people.

Once these well-meaning young journalists get to work, however, things go awry, and, interviewees said, they start doing something rather different from what they set out to do. They start misinforming the public. Not only that, but several interviewees said they think journalists know they are doing this—if not lying, then practicing something akin to PR on behalf of liberals—and choose to do it anyway.

It was in response to the key question of why this immoral turn gets taken that we began to get a variety of answers that, while not necessarily contradictory, were not wholly complementary

either. The answers fell into four main categories, though it is important to note that some interviewees struck more than one of these notes at a time.

1) It’s their bosses’ political agenda

The most common explanation offered for perceived journalistic malfeasance was that these once-idealistic reporters were being compelled by their higher-ups to do wrong. Most interviewees who told this story described not some Herman-and-Chomsky-esque complex process of unspoken rules, but rather explicit orders given by bosses about what to cover and how to cover it, with journalists’ understanding that failure to comply would result either in being fired or not moving up.

Xander, the college student, explained, “It’s not necessarily the journalists themselves, it’s the journalists making a decision of, ‘I need to make money to feed my family, and my bosses are telling me to do narrative storytelling, not real journalism.’ … They were told, ‘We’re going to spend the next four years going after Trump.’ So that’s what they do. And it’s probably nothing personal, maybe on the part of the reporter, he’s just doing what he’s supposed to do to keep his cushy little job at CNN or wherever he’s working.”

The imagined stakes for declining to participate ranged from missing out on promotions to getting fired on the spot. “When it comes down to it, there’s not many people who just want to stay making entry-level salary. They want to move up the ladder. To move up the ladder, you have to play the game,” said Samantha. Arnie explained, “They’re squeezed into a box by their bosses that says, ‘This is the new paradigm of journalism, it is narrative journalism, here’s our narrative. Comply or you’re fired.’ Effectively comply or die, though it’s not death, it’s monetary death.”

Who are these bosses and what do they want? If you’re looking for names, you’ll find ones like George Soros and Jeff Zucker. But generally there was a sense that American media is controlled by a clique of people with a shared interest—for a few interviewees, a very small group whose interest is in a Marxist conspiracy to rule the world; for more, something more like a ruling class of liberal elites. Media bosses either are these folks or are connected to them, and make sure journalists tell their preferred story.

That journalists would abandon their principles to follow their bosses’ orders was a very easy proposition for interviewees to accept. In a focus group, Evan, who works in sales and shipping, referred to a story about “those CNN leaked conference calls” in which higher-ups set the agenda for the day.16 “You can tell on their conference calls in the morning that they’re being conditioned on what to talk about,” he said. Ph.D. graduate Alesandro, who was in the same focus group, replied, “You get in and you inevitably are forced to push a narrative. I mean, I’m not familiar with what Evan is talking about with that leaked phone call, but I’m sure that it’s true.”

It’s worth noting that there’s some sympathy reserved for journalists in this formulation. “I don’t think Lester Holt wakes up every day and is like, ‘Oh, I can’t wait to fuck the world today,” Alesandro said. This is faint praise, however, and the other explanations interviewees offered for why journalists would sell truth down the river were no more complimentary.

2) It’s sensationalism

Refusing to aid and abet the global Marxist conspiracy is one way for a journalist to lose her job, but of course she could also find herself out of work if her company doesn’t make enough money, and some interviewees pointed to this economic threat as the reason for what they perceived as overheated, overly negative coverage of COVID-19 and some other topics.

There was a sense that in the contemporary, high-competition media environment, journalists feel they need to stand out from the crowd and win attention to survive. “I think it sells newspapers, and I think that it draws people to the broadcasts. … They’re all competing for ratings,” said Stephanie, who works as a consultant for non-profits. “It’s like journalistic Darwinism, where they have to do this sort of thing to compete with social media reporting on the site,” said Stella. A realtor, Chloe, echoed this sentiment, and even conceded that in the current information environment, the consequences of journalists failing to win attention could be dire. Arnie told us: “You need to have a component of sensationalism, otherwise you get ignored and passed up … people start doing what they did starting a few years back, and where all the conspiracy things came from and where QAnon came from, that ridiculous conspiracy theory.”

How do journalists get that attention? Some interviewees said, basically, if it bleeds it leads—you scare people. “I feel like people are more likely to look at an article, or watch a segment about something that’s scary because they might feel like, ‘Oh my gosh, what am I going to do?’” Lily the college student said. Others pointed specifically to political polarization

as an intentional strategy to draw eyeballs. “Whether it’s people on the right or people on the left, if I’m telling the truth, then I’m going to call each side out. I don’t know if I’m going to have an audience, whereas if I’m inspiring that this is the best person ever and the other side is evil, and I think you have that on all the networks,” said Lena, a white teacher. And in the words of Chloe: “It’s, again, not just fear sells, it’s controversy, it’s division, it’s how can I pit this side against the next side?”

Critiques like this just raise the question: Is it the audience’s fault? Does the chicken of audience preference come before the egg of sensationalism? Our interviewees, though attached to the idea that the media are run by a liberal elite out of touch with the masses, struggle with this question as well. Some tried to grapple with the tension between their hypothesis that the media cater to their audience’s worst impulses, and their sense that good Americans hate the media. “They may be misinterpreting what they believe we think is attractive to watch,” said Stella.

In other words, journalists may or may not be correct that they need to lie to survive. But they are perceived as lying to survive.

3) It’s personal

Several interviewees offered a simple, straightforward explanation for journalists’ motives in pinning the pandemic on Trump: He’s mean to them.

“I think Trump coming out, when he was even running I believe he said that the media was the enemy of the people. And by saying that, that kind of put a target on his back,” Xander said. “They feel they are being attacked, which they essentially are. … That’s why they hate him so much, because he’s constantly talking about them.”

The idea that journalists dislike Trump because he attacks them is hard to truly separate, however, from the question of why he attacks them, and the sense many interviewees expressed that journalists perceive Trump as a challenge to the cultural authority and agenda of them and their class. Phil put this directly when we asked whether he thought journalists’ beef was with Trump or something beyond Trump himself: “I think it’s both. I think first of all, it’s him, but then there is the movement that he has created which has scared the hell out of them.”

4) It’s journalists’ political agenda

Multiple interviewees referenced what they viewed as the obvious truth that the vast bulk of American journalists are politically liberal. Chris, a college student, even claimed to have stats: 94 percent, he reported. And interviewees had multiple explanations of how and why the political belief systems of journalists intersect with economic incentives and their bosses’ agendas.

Still, these perceptions could sit awkwardly with the other explanations interviewees offered for journalists’ biased coverage. If journalists distort the news simply to survive economically, or to execute the wishes of their bosses, what is the significance of their being liberals? If they are committed liberals, why do we need to hear about their bosses’ agenda? It’s not that there’s a contradiction here so much as there are multiple stories pointing in the same direction. Journalists’ incentive to distort can seem overdetermined.

Journalists are liberals, our interviewees said, because they were taught to be—the word many used was “indoctrinated”—in school. “These journalists are products of their failed high school and college indoctrination. I can see that. You can see it so clearly. It’s so shameful, that it’s not even being hidden. It’s just open there,” said Jennifer. She explained that the process began as early as grade school: “I think that the public education system has failed our country. I look at it, and I look at how they are being indoctrinated in the schools. In the high schools, in the kindergartens even.”

Rudy, a white small-business owner, elaborated on the content of this doctrine: “They’ve been bred up through, since grade school in some cases, and it’s constant. ‘America is not great. America is racist. The founders are racists.’” This sense of condemnation of traditional America, and conservatives specifically, was understood to be at the center of what it meant to be liberal at all—much more so than a belief in, say, big government or redistribution or abortion rights.

Journalists’ work was understood to reflect these values, but it is important to note that while journalists were thought to believe in liberalism, this is not necessarily the same thing as believing what they say. “I think some journalists, sometimes they do believe what they’re writing, and other times maybe they don’t really quite believe it,” said Lily. In these latter cases, journalists are viewed as committed propagandists lying on liberalism’s behalf.

So when we asked our interviewees why journalists would do something like this, the answer we got was not, for the most part, “Because they are evil people.” It was more an image of deluded, indoctrinated people who believe that what they are doing is good. “They don’t think they’re destroying the country. They think they’re saving the country,” said Mary. She was quite clear, however, that this was no excuse: “We know that, morally, the ends do not justify the means. All those Nazi experiments on humans that gave us all sorts of medical information, it’s not good. Ends do not justify the means.”

Individual journalists, then, are not free of blame in our interviewees’ understanding. But it is striking the extent to which they are seen as subject to the ill motives and practices of the institutions in their lives. Interviewees saw a shared politics and worldview among members of the media that were derived from their fundamental need to “play the game” and satisfy their bosses. The general notion that journalists’ judgments are implicitly shaped by institutional structures is consistent with what many journalism scholars have observed about the influence of routinization.17In other words, it is not so much that our interviewees don’t have a coherent understanding of institutional processes. Rather, they belong to an interpretive community with a very specific idea about the worldview that drives them.

Conclusion: What Can Journalists Do?

Conservatives don’t have much regard for mainstream journalism right now. A major reason for this, our interviews suggest, is that they don’t believe mainstream news outlets have much regard for them.

How this belief came to be so central to conservative self-understanding is a complicated story.18 As many observers have noted, the institutional authority of the news has been weakened by a host of factors, including collapsing ad revenues and consequent newsroom divestment (particularly acute in local news), new competition in a digital media environment, and disruptions of news habits.19 Nikki Usher’s recent book, News for the Rich, White, and Blue, helps to explain why these trends might have contributed especially to the alienation of conservatives from the news, as many of the leading (and surviving) legacy news organizations have identified white, affluent, and liberal people as their core target audience, producing journalism that is most attuned to the tastes and preoccupations of this group.20

We do not believe, however, that conservative distrust of the media can be explained as a spontaneous or inevitable reaction to this news environment. News divestment and nichification have likely contributed to dynamics creating the conditions for anti-news media attitudes, but those attitudes have been—and continue to be—cultivated. The emotional charge of our interviewees’ complaints about mainstream media comes not primarily when they describe news organizations embracing liberal values, or even neglecting conservatives’ views, but when they talk about efforts to shame conservatives and discredit them as legitimate participants in public life. This is where conservative media, and more broadly conservative social networks, come in, iterating and reiterating narratives about “the media.” These narratives speak to fears of ostracism, which resonate with conservative audiences in the context of their geographic and demographic alienation from the media, and, for some, a more general sense that their country is getting away from them.

Our research suggests what has happened now that these narratives have been repeated ad nauseam in a polarized political culture: The story about “the media” has become so familiar and intuitive that individuals like our interviewees don’t need to live in an ideological bubble, nor be misled by misinformation, to interpret the news suspiciously. Suspicion of mainstream journalism is their default setting.

This is why we heard some interviewees say the media displayed an anti-Trump bias in their COVID-19 coverage by focusing on cases rather than deaths, and others say there was an anti-Trump bias in the focus on deaths rather than cases. The point is not that all conservative critiques of the media are contradictory. The point is that suspicion of news organizations’ motives is the starting point for many conservatives. This is an approach to interpreting news that gives journalists the opposite of the benefit of the doubt.

How should journalists respond?

In op-ed pages and heated disputes on Twitter, there are basically two schools of thought about how journalists should approach conservatives going forward. Put crudely, these are “Make Nice” or “Screw Them.”

The “Make Nice” camp draws first on the longstanding journalistic ideal of fairness, and counsels journalists to present “both sides” of political disputes and take reasonable steps to avoid the appearance of partisan bias. This does not necessarily mean the glorified stenography of grabbing quotes from one Republican and one Democrat without adjudication; done well, this approach can offer context and practice verification. But it hopes to counteract media distrust among conservatives with respectful and demonstrably equal treatment. There have also been calls for journalists to go further, and make nice by correcting the fact that they are “out of touch” with “the less affluent, less educated, rural parts of the country, where white voter rage galvanized into votes” for Donald Trump, as former New York Times editor Jill Abramson put it in a 2019 op-ed. They should “cover the facts and truths of their lives” and “soak up the sense and sensibility of under-covered America.”21

The “Screw Them” camp sees things differently. It sees a country suffering from both new crises and long-neglected ones and views the validation—to say nothing of prioritization—of conservative views, which proponents view as informed by misinformation or anti-democratic values, as contrary to the public interest. How is coverage of climate change, for instance, enhanced by the amplification of climate change denialists’ voices? In this view, news outlets should not allow themselves to be exploited by bad faith actors, or lend credibility to racism, sexism, or anti-democratic values, in the name of fairness. They should stand up for what’s right and build a healthier democracy by calling it like they see it.

Both of these models have clear limitations. The prospects for “Making Nice” by rebuilding cross-partisan loyalty using the nonpartisan style of 20th-century newspapers and broadcast networks appear dim.22 It’s not that mainstream journalism can’t be more vigilant in making sure perspectives associated with conservatives are treated respectfully—as appears not to have been the case regarding the possibility of COVID-19’s origins in a Wuhan lab. But there’s little evidence that the suspicious approach our interviewees brought to the news could be substantially eased by correcting such missteps. Coverage, whether or not it meets the highest traditional standards for nonpartisanship, is going to be viewed through the oppositional filter. As literary and cultural studies scholars have been arguing for decades, texts (like news programs) do not simply speak for themselves. The interpretive practices groups bring to those texts bring their own meanings and reactions to life.

As for saying “Screw Them,” not worrying about appealing to conservatives, and producing journalism with clear values and a clear voice, the approach has virtues and much to contribute. Important journalism has been and will continue to be done this way. But if one believes, as many proponents of the “Screw Them” approach appear to, that ceding conservative audiences to right-wing outlets means accepting that many Americans will consume uncontested myths and misinformation, the shortcomings of this strategy are clear. The need for broad social cooperation in the face of, say, the COVID-19 public health crisis shows what a profound problem it is for a significant portion of the population to be divorced from reliable news. Citizens in a society are interdependent, and multi-community societies need journalists—not all of them, but at least some—to find a way to bring better information to and engage forums among a broad, heterogeneous public.

Right now we are spiraling in the wrong direction: the depth of anti-media attitudes makes it tempting for news organizations to abandon efforts to reach conservative communities, which in turn helps drive anti-media attitudes deeper still. Nevertheless, our interviews offer hints that efforts to reach broader audiences could bear fruit. They suggest that the antagonism at the emotional nerve center of conservative complaints about news media is not simply a matter of fundamentally clashing interests. The antagonism is mobilized, and the moments of openness we saw from interviewees—the sympathy for journalists, the appreciation for early pandemic coverage, the skepticism of conservative echo chambers—suggest that this mobilization is less than total. There are elements of our interviewees’ identities beyond their conservative allegiance, and some of those elements yearn for cross-partisan information. The filter is powerful. But it has holes.

Confronting the filter

If one wanted to be cynical about our interviewees’ expressed desire for factual and trustworthy news, one could say that they are simply paying lip service to these ideals, but what they really want is news media that confirms their own biases. This is possible. But consider an alternate possibility: our interviewees are being genuine, but find narratives aligning “the media” with a disdainful and untrustworthy liberal elite to be intellectually and emotionally compelling. Their encounters with mainstream media are themselves mediated through conservative outlets and social networks that constantly reiterate this message. Journalists who wish to reach a conservative audience, then, need to find some way to break through or destabilize this filter. They need to do this, somehow, while being perceived as a hostile force, and while provocateurs scream the filter’s argument at the tops of their lungs. It will be a tall task. But unless and until news institutions tackle it, efforts to reach conservative audiences are likely to be ineffectual or worse.

We don’t believe the right model(s) for confronting the contemporary conservative filter exists yet, and we don’t know exactly what it should look like. But we can imagine some aspects of an approach. Journalists will likely need to counteract the “us” versus “them” boundary work that separates journalists from conservatives, and demonstrate clearer lines between themselves and institutional elites with whom they are currently conflated. They will likely need to appeal to the sense of honor our interviewees associated with encountering diverse viewpoints, to make a case that right-wing media are insufficient, while demonstrating they can curate exchanges and interrogations of differing perspectives in ways that are both meaningful and aesthetically compelling to broad audiences. Journalists will almost certainly need to dismantle the perception that they aspire to shame conservatives and cast them out of polite society, a goal they might pursue in part by contesting the idea that “conservative” is a global identity encompassing geography, religion, culture, etc., so that criticism (or even condemnation) of a discreet conservative viewpoint becomes less likely to register as a dismissal of entire communities.

We acknowledge that these are only the germs of ideas. Strategies will need to be developed, concretized, and tested. We hope our research helps clarify the nature of the challenge. To that end, we will be sharing a companion study offering an overview of projects that attempt to tackle the challenges of polarization and sectarian divisions in a range of contexts, and we hope these may yield some insights.

We acknowledge, too, that what we are describing sounds quite different from the model of professional journalism that became dominant in much of the 20th century. It would be reasonable to contend that “confronting the conservative filter” is not part of journalists’ job descriptions. And it certainly should not be left only to journalists and news outlets. But in a high-choice, digital media environment, news organizations are being forced to think all the time about how to mobilize audiences. If we want a robust participatory democracy, they will also need to find ways to mobilize the many millions who have largely abandoned (or been abandoned by) news media and engage with a range of communities—conservatives, yes, but also historically marginalized groups—alienated from mainstream journalism.

At the end of some of our interviews, we asked participants to imagine that journalists we knew really wanted to regain the trust of conservatives. What should they say or do? We got a hodgepodge of answers. Some interviewees, like Jake, the parole officer, told us we were dreaming. Others talked about objectivity and fairness—“All I want is fairness.” Still others wanted an acknowledgment of wrongdoing, a promise of respect, and transparency about bias. What no one said was that they didn’t care. Our interviewees care about the news, a lot. Journalists should fight to get it to them.

Footnotes

-

-

- 1. Julie Jiang et al., “Political polarization drives online conversations about COVID-19 in the United States,” Human Behavior and Emerging Technologies 2, no. 3 (2020): 200–211, https://doi.org/10.1002/hbe2.202; Jennifer Kates et al., “The Red/Blue Divide in COVID-19 Vaccination Rates Is Growing,” July 8, 2021, https://www.kff.org/policy-watch/the-red-blue-divide-in-covid-19-vaccination-rates-is-growing/; Ariel Fridman, Rachel Gershon, and Ayelet Gneezy, “COVID-19 and vaccine hesitancy: A longitudinal study,” PLOS ONE 16, no. 4 (April 16, 2021): e0250123, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0250123; Emily Badger, “Most Republicans Say They Doubt the Election. How Many Really Mean It?,” The New York Times, November 30, 2020, sec. The Upshot, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/11/30/upshot/republican-voters-election-doubts.html.↩

- 2. Megan Brenan, “Americans Remain Distrustful of Mass Media,” Gallup.com, September 30, 2020, https://news.gallup.com/poll/321116/americans-remain-distrustful-mass-media.aspx.↩

- 3. All names are pseudonyms. Identifying details have been omitted or changed where necessary to maintain the anonymity of interviewees.↩