Sign up for The Media Today, CJR’s daily newsletter.

Once upon a time, a newspaper bought a baseball club.

That was 1981, and the mighty Tribune Company bought the Chicago Cubs, then at one of many low points in its not-especially distinguished history, for $24 million, or about $62 million in today’s dollars.

That was awkward. The question at the time was how candidly or deeply could a newspaper report on one of its parent company’s most visible assets.

The honest answer is, nobody ever knows with this kind of thing. On the surface, things didn’t go too badly. No horrendous journalism scandal comes to mind, and the Sun-Times was there to keep its cross-Michigan-Avenue rival honest on the obvious stories. The Cubs, for their part, thrived under the combination.

But when a newspaper is covering a powerful local institution, the questions go beyond the freedom of columnists and beat reporters to be candid about what they see, which is already a problem, to what’s beneath the surface. After all, we never know what we don’t know. Put it this way: would the Lexington Herald-Leader have uncorked its epic corruption probe of the iconic University of Kentucky men’s basketball program in 1985 had it been owned by the university instead of the great Knight-Ridder chain? The question answers itself.

For that matter, would Lance Williams and Mark Fainaru-Wada have felt quite so free to explore why a formerly lithe Barry Bonds was starting to resemble a float in the Macy’s Thanksgiving Day parade while crushing baseballs into powder like a real-life Roy Hobbs if the Chronicle had been owned by the Giants? Not a latte’s chance on Union Street.

All this is not to say that the sale by The New York Times Company of the Boston Globe and smaller New England papers to John Henry, owner of the uber-iconic Boston Red Sox, for the Filene’s Basement price of $70 million, is a disaster or shouldn’t be allowed happen. Hey, it could always be worse.

Who knows? The man who turned around Red Sox may be just the person to turn around the financial fortunes of the Globe, which has underperformed financially even among a damaged newspaper industry and even as it has more than held its own editorially. (Ken Doctor has the best rundown on the paper’s recent fortunes.) Henry hasn’t said much about how he intends to fix the paper, and it’s fair to wonder if even he knows.

But, sad to say, the conflict of a baseball club owning a newspaper is even more acute than a newspaper owning a ball club. In the latter case, the newspaper was the more valuable asset and its very value at least provided an incentive not to take too many risks with the paper’s reputation. The incentives are reversed when the ball club is many times more valuable than the paper.

The Globe‘s Red Sox writers, many of them brands in their own right, are all saying the right things: that they get the problem and will do their best, and no one doubts that they will. Says Dan Shaughnessy:

There’s an inherent conflict of interest which no one can do anything about,” Shaughnessy said. “All we can hope for is that everyone is allowed to do his job professionally and that we are able to keep our independence.”

Dan Kennedy, a leading figure in New England journalism circles, says the big issue isn’t so much covering the ‘Sawx as a team but as a major civic and business institution that carries a lot of weight around city hall and the state house.

But it goes even beyond that. The backdrop to the deal, even as much as the collapse of the newspaper business, is the rise of the sports business.

The Red Sox, centerpiece of Henry’s closely held Fenway Sports Group, are alone worth $1.3 billion, the 11th most valuable sports franchise in the world this year, according to Forbes. That’s more than twice what the group Henry led, which included NYT Co., paid for it in 2002. Fenway Sports, like other big market franchise owners, also controls its own lucrative cable network, New England Sports Network, to broadcast the games. As has been noted, Henry paid more for a second baseman than he did for the storied Globe.

And sports values have been burgeoning across the board. The average team in Forbes‘s list of the top 50 professional sports franchises is worth $1.24 billion, up a stunning 16% in a year. There are 33 teams worth $1 billion versus 24 last year. Two years ago there weren’t any teams worth $2 billion; now there are five.

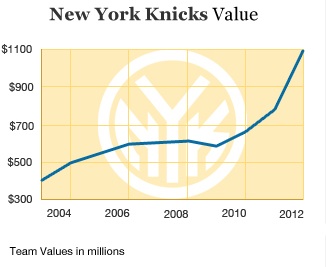

Look what’s been happening to the Knicks lately.

The Knicks!

A sharp uptick in sports-franchise value came, coincidentally, during the collapse of the newspaper business. And while of course news organizations are routinely called on to cover companies much bigger than themselves, the sports industry’s fate is particularly, even uniquely, intertwined with media companies that are both its partners in broadcasting and that purport to cover them. This 2002 paper by scholars from Trent University and the University of Ottawa aptly chronicles what they were already calling, “The global sport mass media oligopoly.” The paper describes the globalization and surging values of sports franchises and the role of media behemoths News Corp., Disney, Time-Warner, among others, in helping to propel them.

Indeed, the ties are getting so close between media and sports that it’s hard sometimes to tell which is the tail and which is the dog. When major college football went on a conference realignment binge a couple of years ago, the big driver was a contract ESPN had struck with the Texas Longhorns that was so big it wound up splintering the Big 12 conference. ESPN, by the way, did a poor job covering a story with itself at the center.

All this is to say the rise of the sports-industrial complex is an important story, and its intimate ties to media giants make it even more so. The question is, who is going to cover it?

Dean Starkman Dean Starkman runs The Audit, CJR’s business section, and is the author of The Watchdog That Didn’t Bark: The Financial Crisis and the Disappearance of Investigative Journalism (Columbia University Press, January 2014). Follow Dean on Twitter: @deanstarkman.