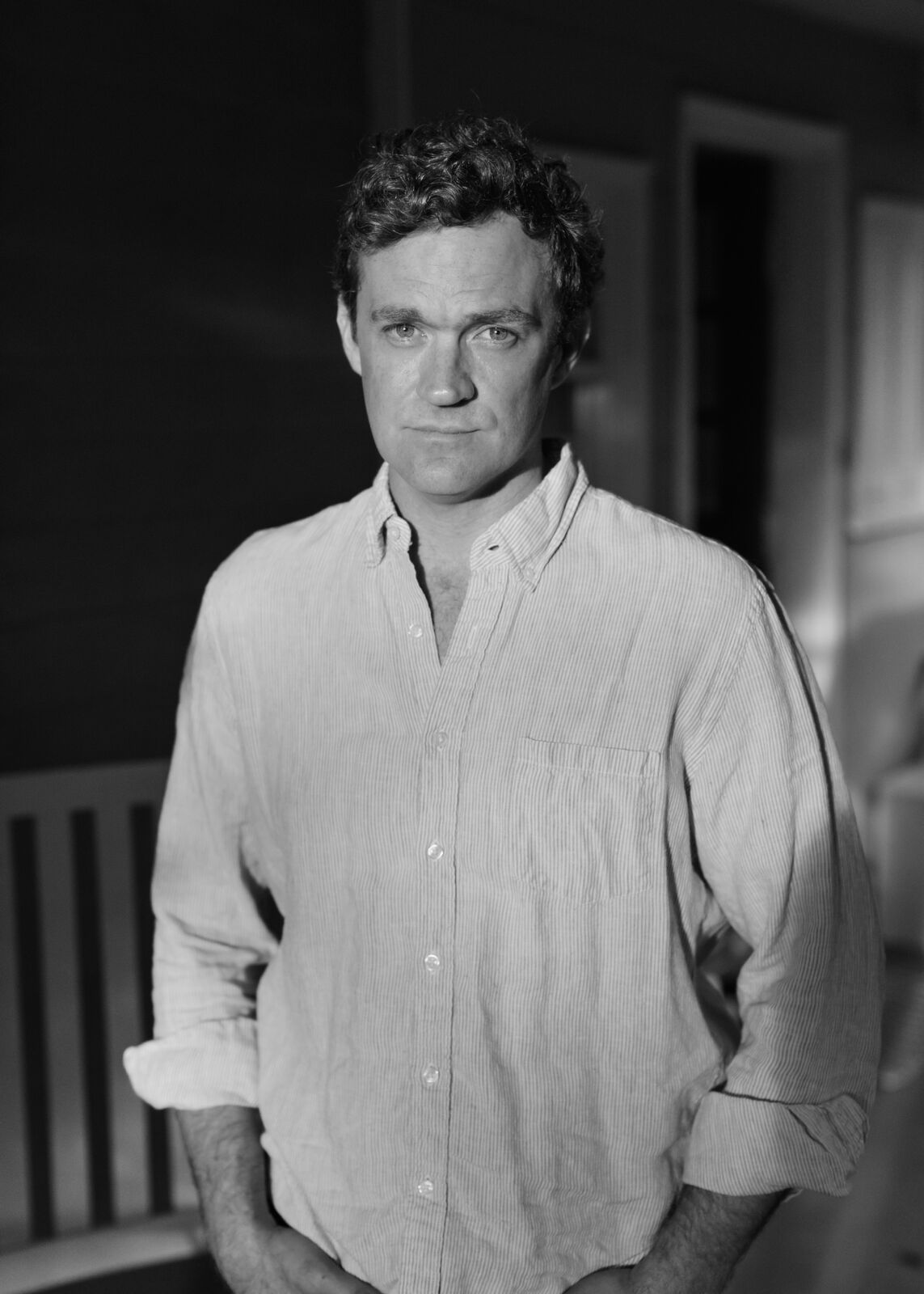

In 2013, Patrick Radden Keefe, a staff writer for The New Yorker, read an obituary in The New York Times of Dolours Price. Price, who died at 61, had been a member of the Provisional Irish Republican Army during the period of Northern Irish history known as the Troubles. It was a bitter, 30-year sectarian conflict that pitted mostly Catholic Irish nationalists against mostly Protestant loyalist paramilitaries and agents of the British government. Keefe was amazed by the life Price had led. “The obituary described her upbringing in an Irish republican family, and then her joining the IRA, and her involvement in some of the worst atrocities in the early years of the Troubles, and then her going off to prison and going on hunger strike, and facing down Margaret Thatcher, and getting out of prison, and marrying a movie star,” he recalls.

Keefe decided to write about Price: first in a 2015 New Yorker article and then, when he realized he’d only just scratched the surface, in a book. The result, Say Nothing, came out in the United Kingdom and the Republic of Ireland last year and will hit American bookshelves in late February. Keefe wraps the story of Price—and other influential Irish republicans—around the case of Jean McConville, a mother of ten from Belfast who was abducted and murdered by the IRA in 1972. (Rumors persist that McConville was a government informant, which her family vigorously denies.) By examining previously unpublished documents and conducting numerous interviews, Keefe made a chilling discovery that enabled him to reconstruct the last moments of McConville’s life.

ICYMI: New York’s Adam Moss talks moving on from his 15-year home

CJR spoke with Keefe about Northern Ireland’s collective silence on the worst of the Troubles, his experience reporting there as an outsider—Keefe is American—and how Britain’s unresolved Brexit mess has loaned Say Nothing an unanticipated new importance. (The following conversation has been edited for length and clarity.)

The title of your book is Say Nothing, taken from a poem by Seamus Heaney. As you have said before, there is this kind of omerta in Northern Ireland around so much that happened during the relatively recent, traumatic period that is your subject. Just how much detective work did you have to do?

I knew from pretty early on that I wanted the title to either be Say Nothing, or Whatever You Say, Say Nothing, and there were moments along the way when I rued the title I had chosen as people either shut me down or said they wouldn’t talk or started talking to me, then changed their minds. When I’m writing for The New Yorker, I often do what we call “write-arounds,” where I don’t have access to the central figure. I certainly had to use the full array of techniques I’ve devised over the years to do that kind of writing in this book, because a number of the central figures—really, most of them—are either dead, or wouldn’t speak with me. So I had to do a fair bit of detective work in terms of trying to collate interviews I was doing with people who knew these characters, and who had been with them during the time periods in question, and then contemporary press accounts. I would hear that Dolours Price had robbed a bank dressed as a nun, and then I’d go back and find that while there’s no mention in the press of Dolours Price doing that, the bank robbery with the nuns was written up in the press at the time. That kind of triangulation was really useful.

Beyond clearly established facts, and the facts you triangulated, there are so many points of contention in Northern Ireland. How did you try and reconcile competing narratives in one account?

What first appealed to me about this story, before anything else, is that it’s a great story. It’s a yarn: it’s a series of incredibly compelling characters thrust into an extreme situation, and you can trace them as they pinball off of one another from the early seventies right up to the present day. So my first imperative was to honor the very good bones of this story. What that meant, in practice, was that there was a huge amount of streamlining that I had to do. There were really two key forms of streamlining. One of the difficulties that I had with this material is that there are so many great stories and I think there’s sometimes a temptation, for any writer, when you’re facing a feast like that, to get a bit digressive, and lose the central thread, because it’s such an embarrassment of riches.

The other issue is that, because this history is so vexed, and because there are so many battles over how to interpret all of these events, I think there’s a tendency to want to qualify and caveat and build in all of the differing interpretations into your main narrative. My feeling was that if I fell for either of those temptations, I would have squandered some of the magic of this story. I wanted to preserve, for a certain kind of reader who isn’t going to read a thousand-page history of the Troubles, the narrative momentum of the tale.

You have some Irish heritage on your father’s side and grew up in Boston when some of this was going on, but you say in the book that you didn’t feel any real connection to the Troubles back then. But you would have been conscious of it, right, because you were in a big Irish-American community?

I think there was probably, in my immediate milieu growing up, a fair amount of… I think the word I use in the book is “ambient” support for the cause of Irish republicanism. But I didn’t see this as my cause by any stretch.

Do you think writing from an outsider’s perspective was a benefit or a weakness?

I went back and forth on this question endlessly over the course of four years, and there were times when I felt, as an outsider, that there were some aspects of this story that I might never understand. But I think it was actually a huge asset. The title of the book is Say Nothing, and there is an entrenched culture of secrecy and restraint. I think there’s also a sense that many people have that they just want to move on, that they’d rather brush things under the rug. But the great thing for me is that there’s almost an “Emperor’s New Clothes” quality to the experience, in which I’m not beholden to any of those rules. I’m an empiricist: what I do is I go out and I talk to as many people as will talk to me, and then I tell the story as I see it, and I do that without any fear, without any feeling that I need to pull punches. Nobody is going to love it unreservedly. There’s no single constituency in Northern Ireland that will embrace this book as their anthem, because my perspective is my own.

How has the reaction been in the UK and the Republic of Ireland?

The reason the book was published earlier over there is because it contained what, over there, was a scoop [Keefe’s identification of the person he believes killed McConville]. In America, the identification of the killer is, I hope, a satisfying ending to the book, but it’s answering a question that nobody was asking. It was fascinating having the book come out over there but it was tricky, because I was changing the story by publishing the book, in a way—I was implicating someone who hadn’t been publicly implicated before in this horrendous war crime.

A week before the book was excerpted in the Sunday Times, I wrote a letter to Jean McConville’s children, telling them, “I think I’ve figured out who killed your mom.” That was an intense experience, and my conversation with Michael McConville [one of her sons] after that was an intense conversation. In some ways I think I’m looking forward to the book coming out in America, because here the book will be treated as a book. It’s not a grenade that I’m throwing into the lives of real people.

You talk in the book about this phenomenon of “whataboutism.” You describe atrocities committed by the British government, and agents thereof, and loyalist paramilitaries. But your book is very much focused on the IRA. Have you had any folks saying, Well, you focus on this, but what about what the other side did?

I anticipated that reaction and I haven’t gotten it. I don’t know whether that’s because, in my own lawyerly fashion, I tried to buttress the book against that kind of charge, by being pretty explicit that this is the story I’m choosing to tell. The book makes no pretense that it’s a balanced, full-spectrum account of the Troubles—there are plenty of those books out there and I recommend them; they’re listed in the end notes. But my intention was to be explicit enough about my objectives in the book that people would just judge the book on its own terms.

To bring this up to date, Brexit has thrown the Irish peace process, if not wide open, then at least into some doubt. As Britain has sought a deal to leave the European Union, one of the central sticking points has been the imperative to avoid reimposing a hard border between the Republic of Ireland—which is in the EU—and Northern Ireland—which, as part of the UK, is coming out. People on both sides of the border are palpably anxious about that prospect; some worry violence could flare up again. Obviously, you couldn’t have imagined this new context when you started reporting. Does it change the meaning of the book in any way?

Well it’s kind of ironic, isn’t it? As I said at the end of the book, I tend to believe that, depending on how Brexit plays out, you may ultimately end up in a situation in which Ireland reunifies at some point, and the precipitating incident will have been Brexit, rather than three decades of terrible bloodshed and strife.

One thing I’ve heard from a lot of younger readers, certainly in the UK, but also in the Republic of Ireland, is: I didn’t really know this history. I was aware of it but didn’t really give it much thought. On some level, I think part of what happened with Brexit was that people forgot about the border, they forgot about the Troubles, and the peace, and the idea that there might be something precarious here. And history came back to get them.

I’m not going to gloat about it. To me, it feels like an unfolding disaster. But it’s helpful for the book: both in that the Troubles are now an issue which is in people’s mind, but also in the sense that part of the point of the book is that the past is alive and dangerous in the present day. I don’t tend to believe that we’re going to get a return to the bad old days of the Troubles; I tend to think that kind of talk is overblown. But if you just forget about the Irish border, you do so at your own peril, as people are now discovering.

ICYMI: Thank you to everyone who can’t redact documents properly

Jon Allsop is a freelance journalist whose work has appeared in the New York Review of Books, Foreign Policy, and The Nation, among other outlets. He writes CJR’s newsletter The Media Today. Find him on Twitter @Jon_Allsop.