A USA Today op-ed column created a stir in recent days. No, not the one supposedly written by President Trump that was followed by a fact check showing many of the claims to be wrong.

This one said that in challenging Brett Kavanaugh’s Supreme Court nomination by supporting his accuser, Dr. Christine Blasey Ford, Democrats had set back the cause of victims of sexual assault. In questioning both Ford’s claim and the Democrats’ pushing of her claim and those of others, the author, Margot Cleveland, said that every false-rape claim “increases the public’s skepticism of sexual-assault allegations. And skepticism quickly hardens to cynicism when the story screams it is a partisan hit job.” (Emphasis added.)

ICYMI: The confusion over ‘rebut’ and ‘refute’

Journalists are supposed to be “skeptical,” but not “cynical.” Both effectively mean to be questioning of facts or motives. But one comes from the point of view of an open mind, and the other from a closed mind. Both trace themselves to ancient Greek philosophers.

The third-century BC philosopher Pyrrho and his followers apparently believed that knowledge was unknowable, meaning there was no guarantee that one could ever ascertain the truth of something. (It’s ironic that Pyrrho left virtually no writings, and so what he actually believed is open to doubt.) They wanted to achieve a state called “ataraxia,” which the Oxford English Dictionary defines as “Freedom from disturbance of mind or passion; stoical indifference.” It’s not that they didn’t care; it’s that they didn’t want to worry about it. “Skeptic” is derived from a Greek word meaning “questioning” or “thoughtful.” (Pyrrho the philosopher is not related to King Pyrrhus of Epirus, whose wars against the Romans in the third century BC inflicted greater casualties on his own armies, and led to the phrase “Pyrrhic victory.”)

By the early 17th century, a “skeptic” (“sceptic” in British English) was someone who “maintains a doubting attitude with reference to some particular question or statement. Also, one who is habitually inclined rather to doubt than to believe any assertion or apparent fact that comes before him,” the OED says.

The OED definition of “skeptic” that is closest to journalism’s heart, though, is “A seeker after truth; an inquirer who has not yet arrived at definite convictions.” Healthy skepticism allows someone to accept as fact that which has been proved beyond a reasonable doubt.

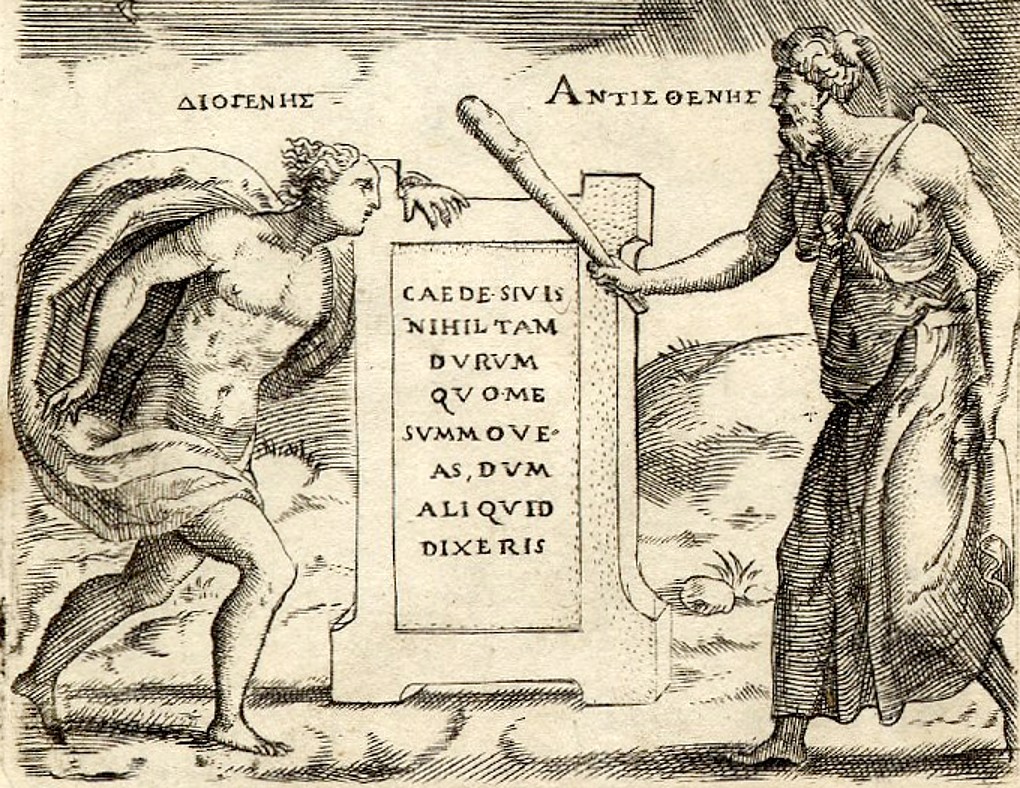

Unhealthy skepticism is a tendency to believe everything is “fake news” or wrong, which can lead to “cynicism,” That, too, comes from ancient Greek philosophy. A pupil of Socrates, Antithenes, founded the Cynics, who, as the OED says, had “an ostentatious contempt for ease, wealth, and the enjoyments of life.” In Greek, the name of the philosophy was kynikoi, or “doglike ones,” after a place where Antithenes taught. In the late 15th century, the OED says, the “cynic” emerged as “A person disposed to rail or find fault; now usually: One who shows a disposition to disbelieve in the sincerity or goodness of human motives and actions, and is wont to express this by sneers and sarcasms; a sneering fault-finder.”

The Associated Press Stylebook has a simple differentiation: “A skeptic is a doubter. A cynic is a disbeliever.”

The next step after “cynicism” is becoming “jaded.” Where “cynics” might be sneering and actively doubting something, people who are “jaded” are just so exhausted that they have become apathetic. They just don’t care anymore.

In the 14th-century Prologue of the Nun’s Priest’s Tale, Chaucer wrote: “Be blithe, though thou ryde upon a jade.” Most modern translations make that “jade” a “nag,” or a sorry excuse for a horse. In the early 17th century, the verb “jade” meant to exhaust or wear something out, the OED says, applied mostly to horses but also to people.

The adjective “jaded” first appeared in English in the late 17th century to mean “fatigued by overwork” or “exhausted.” The OED has no definition for the modern “jaded” that arises from “cynicism,” but Merriam-Webster defines that as “made dull, apathetic, or cynical by experience or by having or seeing too much of something,” and uses as examples “jaded network viewers” and “jaded voters.”

“Skeptics” are healthy for journalism, but “cynics” are not. And though the 24-hour news cycle might exhaust you, don’t let it “jade” you. “I really don’t care, do u?” jackets are for others to wear.

ICYMI: CJR editor says he’s been irked by one common critique of the NYT Trump investigation

Merrill Perlman managed copy desks across the newsroom at the New York Times, where she worked for twenty-five years. Follow her on Twitter at @meperl.