In January 2014, Marwan Hisham invested $2,000—his earnings from his family’s tomato and eggplant harvest—in a satellite dish, which he installed on the top of his uncle’s café in Raqqa. Hisham’s hometown had just become the de facto capital of the so-called Islamic State. Satellite internet could drive business for the café; however, as foreign jihadists began frequenting the location, Hisham saw a journalistic opportunity. He could go undercover, taking notes and documenting his interactions with the fighters.

“Fighters speaking different tongues from different countries and with skin of different colors, all were unified in their thirst for infidels’ blood and our bandwidth,” Hisham writes in Brothers of the Gun, his recently released memoir, a journalistic and artistic collaboration with US-based artist Molly Crabapple. “As I hustled around the café, setting up customers and handling complaints, I overheard their constant chatter: They discussed the front lines, the challenges facing al-Dawlah, the ignorance of the ordinary people and their Jahaliyya habits, and the difficulty of finding brides.”

ICYMI: How journalists may be putting ISIS suspects at risk of abuse

The same satellite enabled Hisham to meet Crabapple—who he refers to as “the artist” in their book—on Twitter. The two struck up a correspondence and then a friendship. She approached him with a journalistic proposition: Would he covertly photograph scenes of daily life in Raqqa and send them to her? She could draw scenes from his photos and, with his writing, they could provide a singular account of daily life in the now-notorious city.

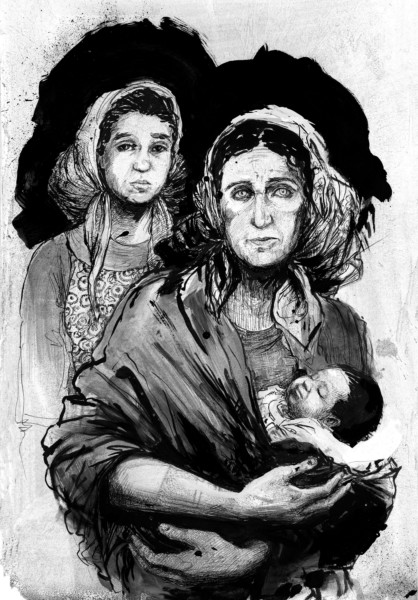

Image courtesy of Molly Crabapple

Crabapple’s proposition had terrifying stakes. If caught, Hisham could be labeled a spy and killed. “My knowledge of digital security is pretty average, but I had a few ‘silly tricks’ to keep myself safe while working,” Hisham says now. “I would download ISIS-approved nasheeds [one of the only forms of music that the Islamic State allowed], which I would play in case someone saw me taking a picture. That way, if an ISIS guy questioned me, I could simply delete the picture and play the video.”

In October, Crabapple published “Scenes From Daily Life in the De-Facto Capital of ISIS” in Vanity Fair online. To ensure Hisham’s safety, his name was omitted from the work. But he was hooked on what he would later refer to as the “art crime.” Hisham sold the satellite dish—US coalition airstrikes were targeting ISIS hangouts by then, and the cafe was nearly dead—and traveled to Mosul for a second covert collaboration with Crabapple, and then to Aleppo for a third. By the time Hisham made it back to Raqqa, the foreign fighters to whom he had once sold bandwidth had become paranoid, raiding homes and looking for spies and disbelievers. For Hisham, it was time to go.

Crabapple bends the rules of traditional visual journalism and pieces together Hisham’s memories to recreate scenes which would have been impossible for a traditional war photographer to capture.

Like many Syrians before him, Hisham went to Istanbul, where he was able to meet with Crabapple regularly. The two began to collaborate on what would become Brothers of the Gun. In addition to using his cell phone photos, Crabapple interviewed Hisham extensively about his memories of certain places, cross-referencing his stories with hundreds of YouTube videos, carefully poring over them frame by frame until Hisham confirmed that her illustration resembled a scene from Syria.

“Collaborating with Marwan was the hardest and most precious experience of my artistic life,” Crabapple says. “To see through someone else’s eyes, and subsume your voice as a writer in theirs, to try again and again to get things right in the service of truth, these are challenging things, but ones I’m so proud and lucky to have done with one of my best friends.”

Image courtesy of Molly Crabapple

A FEW MONTHS AFTER HISHAM LEFT RAQQA, the United States Central Command announced the beginning of Operation Inherent Resolve. During the aggressive military campaign, a US-led coalition bombed ISIS targets in Mosul and Raqqa; after, a number of military groups— the Peshmerga, the Iraqi Army, and the Syrian Democratic Forces—cleared the cities of any remaining ISIS presence. The announcement of Operation Inherent Resolve brought to the region dozens of journalists, who were eager to bear witness to what was certain to be a historic war and understand the machinations of the notorious terrorist group. I was one of them.

The Western media was already salivating over ISIS stories. Major television networks threw thousands of dollars per day towards fixers, translators, and security consultants, bought embeds in elite units, and traveled to the frontlines in full-on convoys. Desperate to compete, young freelancers pooled their money together, splitting the cost of a fixer three or four ways, hoping against hope that no one got injured, and that they didn’t all return with the same story.

What did we come back with? There were the requisite “war stories” swapped over cheap beers at one of a handful of Erbil’s drinking establishments. There were photographs of harrowing scenes—makeshift medical clinics and wounded civilians, proud young men aiming AK-47s towards the enemy in the distance. Writers shared stories of the amazingly resilient characters they met, from women in refugee camps victoriously ripping off the khimar face veils to jubilant children returning to school for the first time in almost three years.

But in the frenzy of gaining access to the frontline—and, later, to Mosul and Raqqa—many of us realized later that we missed half the story. What was happening on the other side? What did it look like to lose the war? Beyond the gruesome details, what was ISIS, and what motivated it?

Without being able to access the Islamic State itself, reporters were forced to rely on survivor testimonies and salvaged documents to cross-reference and piece together what happened during the preceding two years.

“Reporting from inside of the Caliphate was essentially impossible,” says freelance journalist and photographer John Beck, a freelancer who closely followed the rise and fall of the Islamic State for publications including GQ and The Sunday Times.

“Correspondence with ISIS members was difficult from the beginning of the group’s existence, and became more difficult over time,” says Beck. “As the battles for Mosul and Raqqa progressed, it became far easier to create a bigger picture, both through interviews with civilians who had escaped ISIS territory and documents that were found. But in all cases, careful verification and cross-referencing was required.”

Without being able to access the Islamic State itself, reporters were forced to rely on survivor testimonies and salvaged documents to cross-reference and piece together what happened during the preceding two years. Such actions sometimes raised legal, moral, and ethical dilemmas—take, for instance, this piece by The Intercept, which examines the decision by New York Times reporter Rukmini Callimachi to take thousands of ISIS documents to the US to report her podcast Caliphate. [Disclosure: My work has also appeared in The Intercept.] At the Times’ Reader Center, Callimachi and her editor, Michael Slackman, responded in detail to questions about the decision to take the documents.

Reporters have interviewed prisoners of war, something that human rights advocates argue could constitute conducting an interview while someone is under duress. Many survivors were eager to tell their stories to journalists, but had experienced an enormously traumatic series of events. Is it right to interview someone—and grill them on the details—when something so traumatizing and surreal is so fresh in their minds?

“I think there was a huge appetite for that story [ISIS] at that time, and there were also untold elements to this story,” says Cathy Otten, a British journalist and author of With Ash On Their Faces: Yezidi Women and the Islamic State. With many journalists eager to go to the front lines, Otten focused on telling the stories of ISIS’s survivors, specifically Yezidi women living in Northern Iraq. However, the more hideous stories she heard of rape and enslavement, the more she wondered about the perpetrators.

“When you look at why someone joined ISIS, you get labeled as a sympathizer, but I think it is important to look at why this happened,” she says. With the help of an Iraqi colleague, Otten tracked down the family of a deceased ISIS commander notorious for participating in the slave trade in Anbar. But while she interviewed as many family members and friends who could speak to his history and character as she could, it was still challenging to piece together a picture of something without seeing it with her own eyes.

“This is where the work of an Iraqi, or any local journalist is so important,” Otten says. “While what we add is valuable, we will never have the depth and the knowledge that an Iraqi journalist—or someone who lived in the place you are reporting—has.”

Brothers of the Gun disrupts the traditional model of war correspondence. Hisham’s detailed anecdotes of jihadists chatting about their daily lives in a modern day insurgency would be difficult to recreate through anything other than first-hand testimony. Without his observations and his writing, such conversations would have otherwise been forgotten. By meticulously researching and cross-referencing her illustrations, Crabapple bends the rules of traditional visual journalism and pieces together Hisham’s memories to recreate scenes of Yezidi women in a cafe in Raqqa, and a young man being pulled from the rubble after a US airstrike—both of which would have been impossible for a traditional war photographer to capture.

While Hisham might be credited as the author and Crabapple as the artist, it is clear through these poignant scenes that each played a role in both the prose and the artwork. The resulting collaboration hacks war reporting as many of us have known it, and grants new access for an audience whose members include art lovers and Islamic State analysts. Together, they breathe life into a crucial period of history and ensure that it will never be forgotten.

ICYMI: NYT‘s Rukmini Callimachi on covering ISIS

Anna Lekas Miller is a freelance journalist who covers stories of how people survive war and borders. Her work has been published in The Intercept, The Nation, The Daily Beast, CNN, and many others. Follow her on Twitter @agoodcuppa.